Contents

Introduction

Pathology

Clinical Features

Investigations

Treatment

Introduction

Tuberculosis is a disease of diverse manifestations that is caused by infection with mycobacterium tuberculosis. The incidence in Britain is approximately 10 per 100,000 per year but this figure is subject to fluctuations. The incidence is much higher in developing countries, where it may be in the region of 40 per 100,000 per year. It is estimated that one third of the population of the world are infected by TB and that the infection accounts for 6% of all deaths globally.

Various factors increase the risk of contracting tuberculosis

- Travel to high risk areas (Indian subcontinent)

- Alcoholism

- Immunosuppression

- Homelessness

- Residency in an institution

- Medical work

Mycobacterium tuberculosis is not the only species of mycobacteria which can produce disease in humans. Leprosy is caused by mycobacterium leprae. Mycobacterium bovis, which can be contracted by drinking unpasteurised milk, likes to take up residence in the terminal ileum and caecum where it can mimic Crohn's disease. Various other mycobacteria, such as mycobacterium avium-intracellulare, can be pathogenic in immunocompromised people. The term TB is sometimes applied to cover infection by all of these different species of mycobacteria (with the exception of mycobacteriym leprae). Infection by opportunistic mycobacteria like mycobacterium avium-intracellulare is referred to as atypical TB.

Pathology

Mycobacterium tuberculosis is a slender, non-motile, non-sporing, aerobic beaded bacillus that does not stain with the Gram method and must instead be approached with the Ziehl-Nielsen or auramine techniques. The method of the ZN stain endows the mycobacterium genus with the name of acid fast.

As well as resisting the Gram stain mycobacteria have unusual culture requirements and will not grow on normal media. Instead they require Lowenstein-Jensen medium. The culture needs to be left for 6-8 weeks before it can reliably be deemed to be negative.

|

The pleasantly green Lowenstein-Jensen medium. Colonies of mycobacteria are present.

Image courtesy of Wikipedia

|

Mycobacterium tuberculosis tends to be spread by the respiratory route. It has been suggested that the organisms are susceptible to ultraviolet light and that transmission seldom occurs during daylight.

The abillity of mycobacteria to cause disease is linked to one of their special abilities. Unlike other bacteria, mycobacteria are able to survive within the phagosomes of neutrophils and macrophages. Within the phagosomes mycobacteria prevent the fusion of the lysosome with the phagosome and thus stop the neutrophil or macrophage from blasting them with the various destructive substances that are contained within the lysosome.

Faced with a resilient foe the immune system calls in some heavier weaponry. The macrophages co-ordinate their efforts to form

granulomas. Macrophage multinucleate giant cells are featured in these granulomas. The granulomas may finally be able to kick mycobacterial butt but even if the micro-organisms resist this assault the granulomas can contain them and stop replication. In a healthy person this containment is highly efficient.

The activation of the macrophages to granuloma mode requires effective

T helper lymphocyte function.

The granulomas of tuberculosis are classically described as caseating. The term caseation actually applies to the macroscopic appearance of a form of necrosis which resembles cheese. Strictly speaking, this cannot be discerned microscopically and the granulomas can only be deemed to exhibit necrosis. Nevertheless, the terms caseating granulomas and non-caseating granulomas are entrenched. The finding of a caseating granuloma in a histopathological specimen essentially equates to 'TB until proven otherwise'. Caseation is highly sugggestive of tuberculosis but is not definitive. Various granulomatous disease can feature necrotic granulomas. Conversely, the absence of necrosis in the granulomas does not exclude tuberculosis.

The interaction between the T cells and the macrophages, together with the other cytokines secreted by these cells also stimulates local fibrosis.

Much of the pathology of tuberculosis is based upon the combined effects of caseous necrosis (destruction), granulomas (damage to adjacent tissues and a mass effect at the microscopic level) and fibrosis (damage to, distortion of and loss of the fibrosed tissues and also a mass effect). This coalition of damage, distortion and fibrosis allows tuberculosis to cause a variety of problems in the affected organ. When combined with the ability of mycobacterium tuberculosis to affect almost any organ, TB can produce almost any symptom in any organ and was historically known as the 'great mimic'.

Despite its potentially diverse manifestations, mycobacterium tuberculosis is a creature of habit and has preferred patterns of infection. The lung is top of the organism's list.

The initial infection of the lungs by mycobacterium tuberculosis tends to involve the peripheral aspect of the middle zone. In an immunocompetent individual this

primary infection is dealt with quickly and should produce only a small focus of granulomatous chronic inflammation that is known as the Ghon focus.

Drainage of some of the mycobacteria to the hilar lymph nodes can produce granulomatous lymphadenopathy. The combination of these lymph nodes and the Ghon focus is called the Ghon complex.

If the patient's immune function remains adequate the infection may never progress past the primary stage. The symptoms of the primary infection are usually indistinguishable from a cold or flu and so the person may never realise they have ever had TB.

Problems arise if the immune containment of the infection becomes impaired or the patient suffers reinfection when their immune system is not as effective. Debate exists as to which of these events occurs if the TB kicks off at a late date to give post primary TB.

Post-primary tuberculosis favours the upper lobes of the lungs. The process is one of granulomas, caseation and fibrosis. Depending on how well the immune system deals with the problem there may be only mild degree of fibrosis or there can be marked fibrosis, often with cavitation.

Cavitation occurs in tuberculosis due to caseous necrosis. If there is marked caseation the granulomas can become confluent. Sooner or later the coalesced volumes of necrosis become sufficiently large that they collapse and form a small cavity. If the immune system continues to fail to hold the mycobacteria in sufficient check then these small cavities can fuse to form larger cavities; fibrosis occurs at the edge of these cavities.

The cavitation destroys lung tissue and the fibrosis distorts and shrinks the adjacent lung tissue. Bronchiectasis can also occur.

If the response to the mycobacteria is somewhat inept then a tuberculous bronchopneumonia results from spread of the mycobacteria through the airways.

|

|

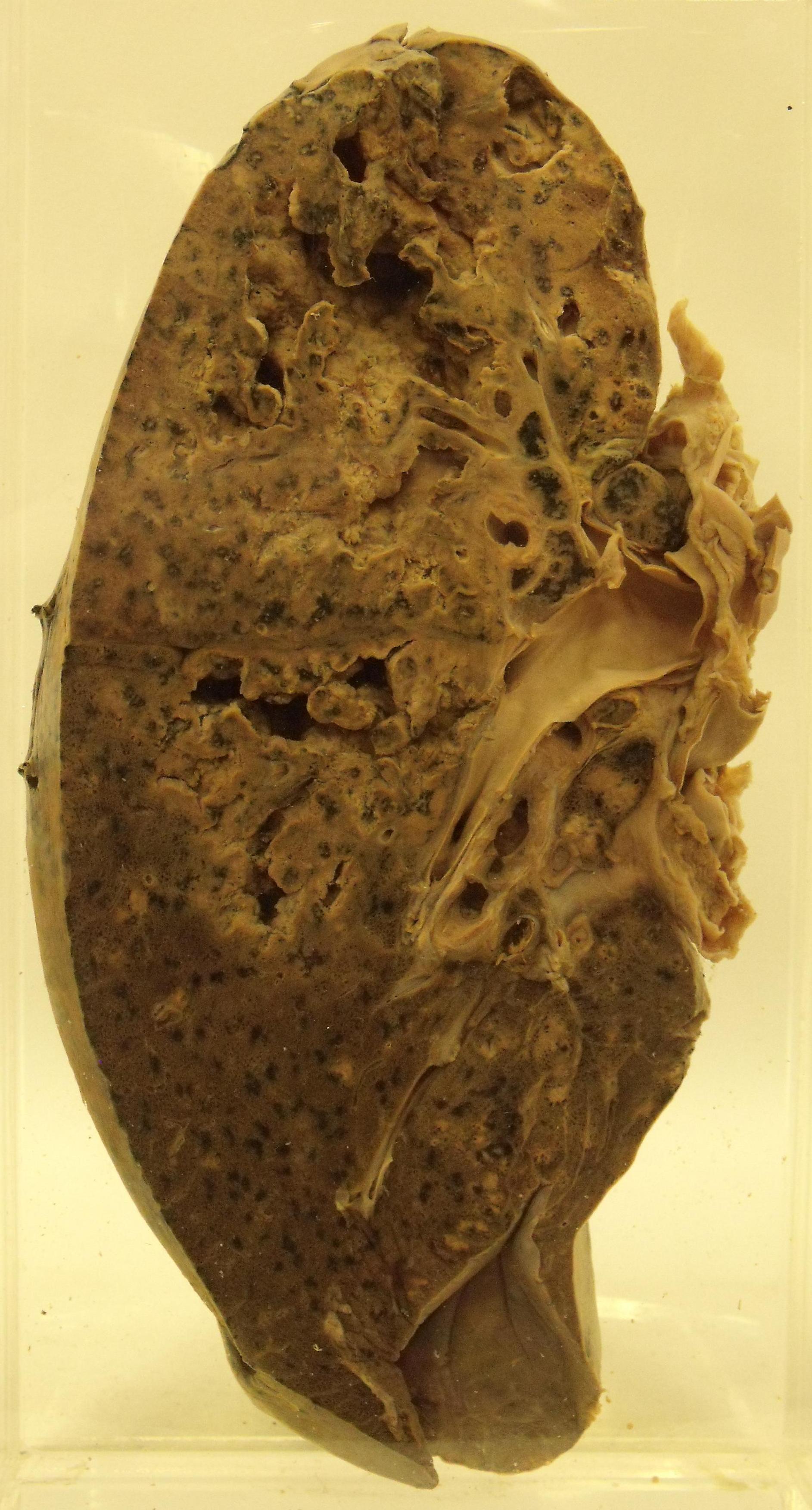

|

Post primary tuberculosis showing cavitation

|

Tuberculous bronchopneumonia

Both images courtesy of Dr Carol Shiels

|

The pathology of tuberculosis in other organs is similar to that of pulmonary post-primary TB. The cervical lymph nodes are a popular alternative venue for mycobacterial infection and can also be involved in conjunction with the lungs. The terminal ileum and caecum are more likely to be involved by mycobacterium bovis than mycobacterium tuberculosis but this part of the bowel is one of the regions of the body more frequently affected by mycobacterial infection.

The stomach is probably one of the most resistant organs to mycobacterial infection.

Miliary tuberculosis is a form of TB that develops when the immune system has entered complete chocolate teapot mode and cannot cope with the mycobacteria at all. It tends to be seen in young children or the heavily immunocompromised. The mycobacteria cut a swathe throughout the body, with the lungs, liver and spleen bearing the brunt. Multiple small foci of necrotic infection only a few millimetres across riddle the affected organs. One or more luminaries in history believed that these foci looked like millet seeds and therefore bestowed the adjective miliary on these form of TB.

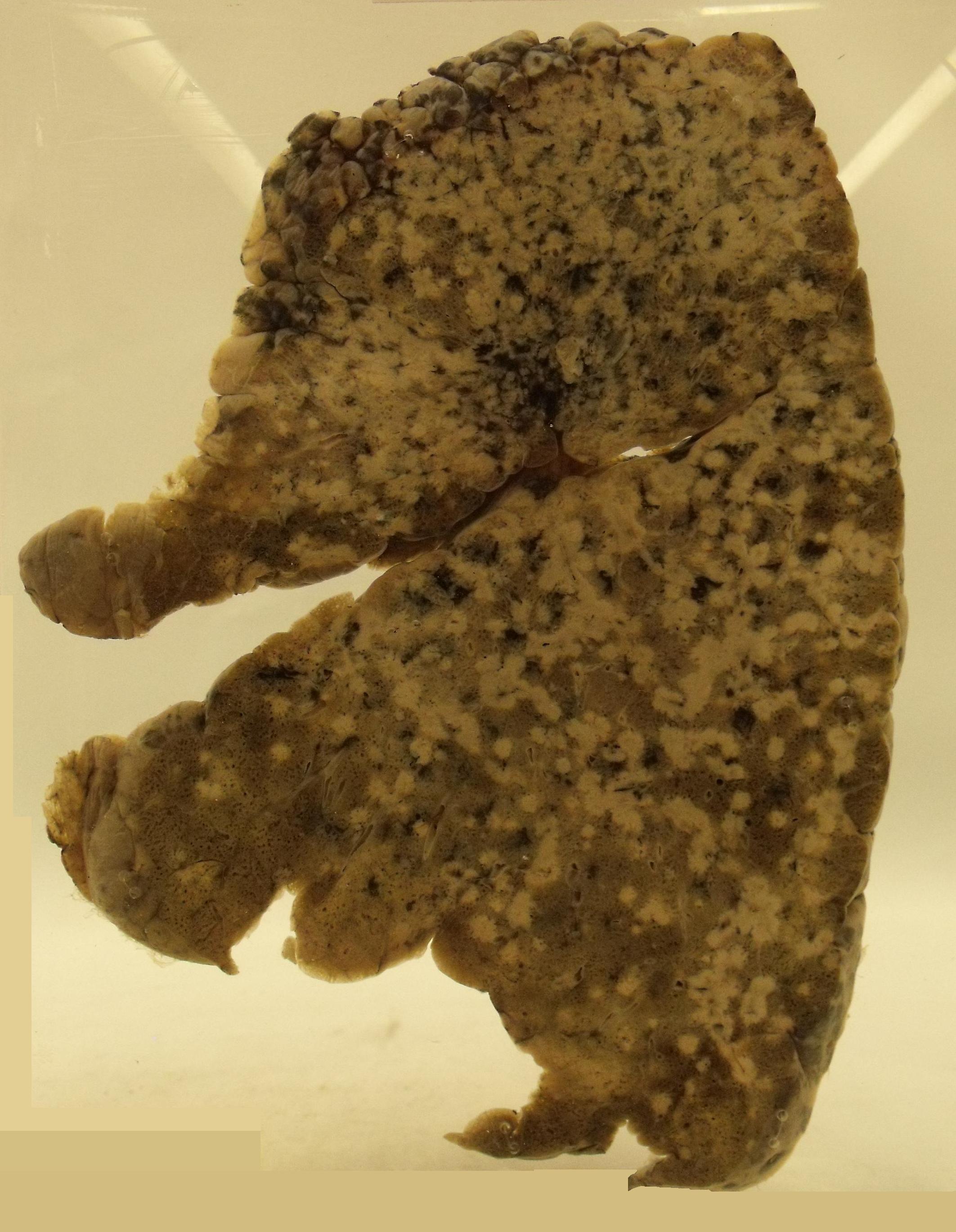

|

Miliary TB affecting the lung (left), spleen (top right) and liver (bottom right)

Image courtesy of Dr Carol Shiels

|

Clinical Features

General

The organ specific manifestations of tuberculosis are often accompanied by systemic symptoms such as fever, night sweats and weight loss.

Lungs

The most common symptom of pulmonary tuberculosis is a dry cough that is sometimes accompanied by haemoptysis. On examination there can be crackles heard in one or both apices of the lungs. The trachea may be deviated to the affected side, having been pulled there by the fibrosis. The percussion note may be dull.

Extension of the infection to the pleura gives a pleural effusion and this can be the presenting problem.

Cavities in the apex of the lung can be colonised by the fungus aspergillus. Proliferation of the fungus yields a ball of hungal hyphae known as an aspergilloma. Occasionally this ball can erode through into a large blood vessel and cause massive haemoptysis.

Larynx

Laryngeal tuberculosis is rare and tends to indicate that the disease has taken a strong hold. The spread of the infection to the larynx is from direct transmission via coughing up sputum. Patients who have laryngeal tuberculosis are highly infectious.

Haematoreticular

Lymphadenopathy is frequently encountered in tuberculosis. The cervical lymph nodes are a common site. In severe cases the caseous necrosis can track through to the surface of the skin to give a fistula. The lymph nodes in such cases are usually matted.

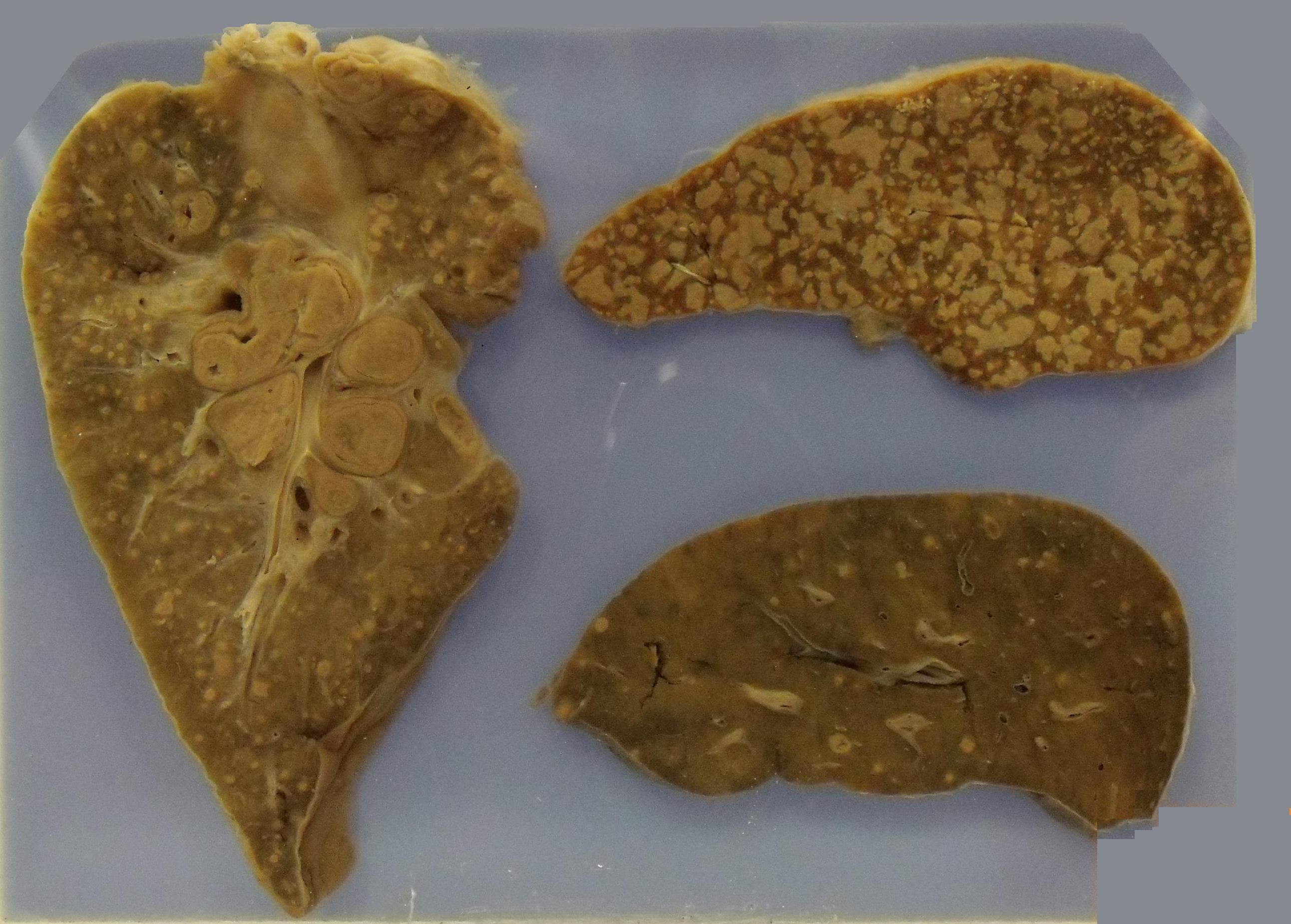

|

Mesenteric lymph nodes enlarged by tuberculosis

Image courtesy of Dr Carol Shiels

|

Heart

Cardiac involvement is unusual but typically takes the form of a pericardial effusion. The fibrosis of tuberculosis can cause constrictive pericarditis.

GI Tract

Mycobacterial infection of the GI tract tends to present like Crohn's disease of the terminal ileum.

Involvement of the peritoneum may cause ascites.

Nervous System

Mycobacterium tuberculosis can produce meningitis. Tuberculous meningitis is not as rapidly progressive as bacterial meningitis but can still ultimately be fatal. The exudate in tuberculous meningitis is very high in protein and viscous. The fibrotic response to the meningitis can cause obstructive hydrocephalus and/or cranial nerve palsies.

Tuberculomas are granulomatous masses that are formed in response to mycobacterial infection. They behave as space occupying lesions.

Genitourinary System

Various problems can occur in the urinary system, including renal papillary necrosis.

The potential manifestations in the reproductive system are also diverse. Tuberculous salpingitis can result in infertility.

Musculoskeletal

Musculoskeletal tuberculous is mentioned to cover two particular manifestations. Pott's disease of the spine is tuberculosis of the vertebral column. It tends to affect the midthoracic vertebrae and can cause vertebral collapse.

In some cases vertebral tuberculosis may track down the psoas muscle to form an abscess in the upper thigh.

Endocrine

Infection of the adrenal gland can destroy the adrenal tissue and produce

Addison's disease.

Skin

Unlike leprosy, which is very fond of the skin, tuberculosis usually does not pay much need to the skin except in long-standing, untreated disease. The possible manifestations inlude erythema nodosum and lupus vulgaris.

Investigations

The central aim of the investigation of a possible case of tuberculosis is to obtain definitive evidence of mycobacterial infection. In the case of pulmonary TB the first port of call is typically microbiological analysis of several sputum samples.

If lymphadenopathy is present this can be biopsied and material sent to both microbiology and histopathology. Even with the ZN stain the organisms are very shy and it is quite possible for histopathological analysis to disclose necrotic granulomas without any acid fast bacilli being discernible. This reticence of the mycobacteria requires culture or PCR to amplify the number of bacteria to a level at which they can be detected and thus fresh tissuel should be sent to microbiology whenever possible.

If the clinical context is appropriate and histopathology demonstrates necrotic granulomas, a diagnosis of tuberculosis may need to be made on ground of probability even if acid fast bacilli are not seen. Nevertheless, this does not obviate the need to obtain a microbiological diagnosis because microbiological examination can determine the sensitivity of the organism to various antibiotics. The rise in drug-resistant TB and the possibility of the patient being allergic to one or more of the first choice antibiotics can make ascertaining the antibiotic sensitivities of the organism invaluable in some cases.

Other samples may be obtained for microbiological or histopathological evaluation, depending on the organs that are affected.

The Mantoux test evaluates the strength of the immune response to a subcutaneous injection of mycobacterium tuberculosis derived protein and utilises type four hypersensitivity. Patients who have previously been exposed to TB (or the BCG vaccination) will have a good, prompt response. A negative response will be found in people who have never been exposed to TB or who have defective cell mediated immunity; the test therefore tends to be negative in miliary TB. The Heaf test is a variation on the same theme. If a patient has reasonable immune function and is suspected of having established tuberculosis a negative Mantoux test would be unusual.

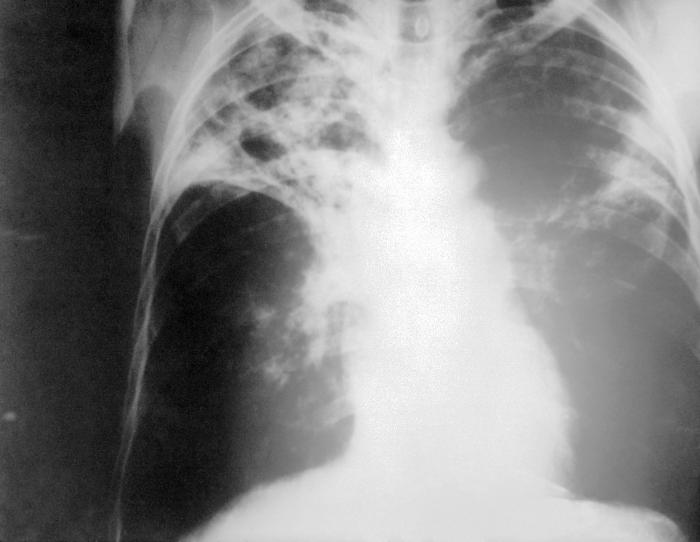

While the hunt for the mycobacteria is taking place a chest X-ray is useful in evaluating the lungs for evidence of changes that could be due to tuberculosis. Apical fibrosis, with or without cavitation, is the classical finding.

|

|

Two chest X-rays of tuberculosis

Images courtesy of Wikipedia

|

Treatment

Mycobacterium tuberculosis is a stubborn organism that does not succumb readily to single agent antibiotic regimens. Resistance develops quite quickly if only one drug is used so combination treatment is employed.

The opening salvo is with triple or quadruple therapy. The first three agents are commonly rifampicin, isoniazid and pyrazinamide. Ethambutol is the fourth antibiotic that is added if necessary. The triple / quadruple therapy is intended to stop the infection in its tracks and deal it a heavy blow.

The triple or quadruple therapy is followed by dual therapy. Rifampicin and isoniazid are the most popular double act. Double therapy is intended to finish the job of erradicating the infection.

Triple / quadruple therapy is given for two months in pulmonary TB; dual therapy is administered for a further fourth months. Longer courses of treatment and different transition points may be required if other organs are infected. For example, tuberculous meningitis is treated with anti-tuberculous antibiotics for at least a year.

The back up drug if any of the front four cannot be used is streptomycin. Unfortunately streptomycin has to be given by intramuscular injection. Beyond streptomycin are a collection of seldom encountered drugs that tend only to be invoked when things become really problematic.

As well as treating the patient it is important to trace contacts who might also be infected.

Tuberculosis is a notifiable disease.

Prevention of tuberculosis is by administration of the BCG vaccine. This is usually given around the age of 13 years.