Contents

Introduction

Gastric adenocarcinoma is a malignant tumour of the glandular epithelium of the stomach. The incidence in the UK is around 20 per 100,000 per year (the highest incidence in the world is in Japan, where the disease occurs over four times as commonly as in the United Kingdom). The male to female ratio 2 : 1. The tumour tends to present after the age of 60 years.

There are several risk factors for gastric adenocarcinoma.

- Helicobacter pylori infection

- Family history

- Smoking

- Alcohol

- Dietary nitrosamines and polycyclic hydrocarbons (smoked food)

- Pernicious anaemia

- Familial polyposis syndromes

- Blood group A

Of these risk factors the most important is infection by helicobacter pylori.

Pathology

Gastric adenocarcinomas can be fungating, polypoid masses, sessile plaques or flat ulcers. Although there are endoscopic features which suggest that an ulcer is malignant rather than benign (malignant ulcers tend to have raised, rolled edges and the gastric rugae do not converge on them in an orderly fashion), reliable macroscopic distinction is not always possible; .

Appximately 50% of the tumours occur in the antrum or pylorus.

|

|

An opened gastrectomy specimen in which a sessile, ulcerated tumour is present (indicated by the four black arrows).

|

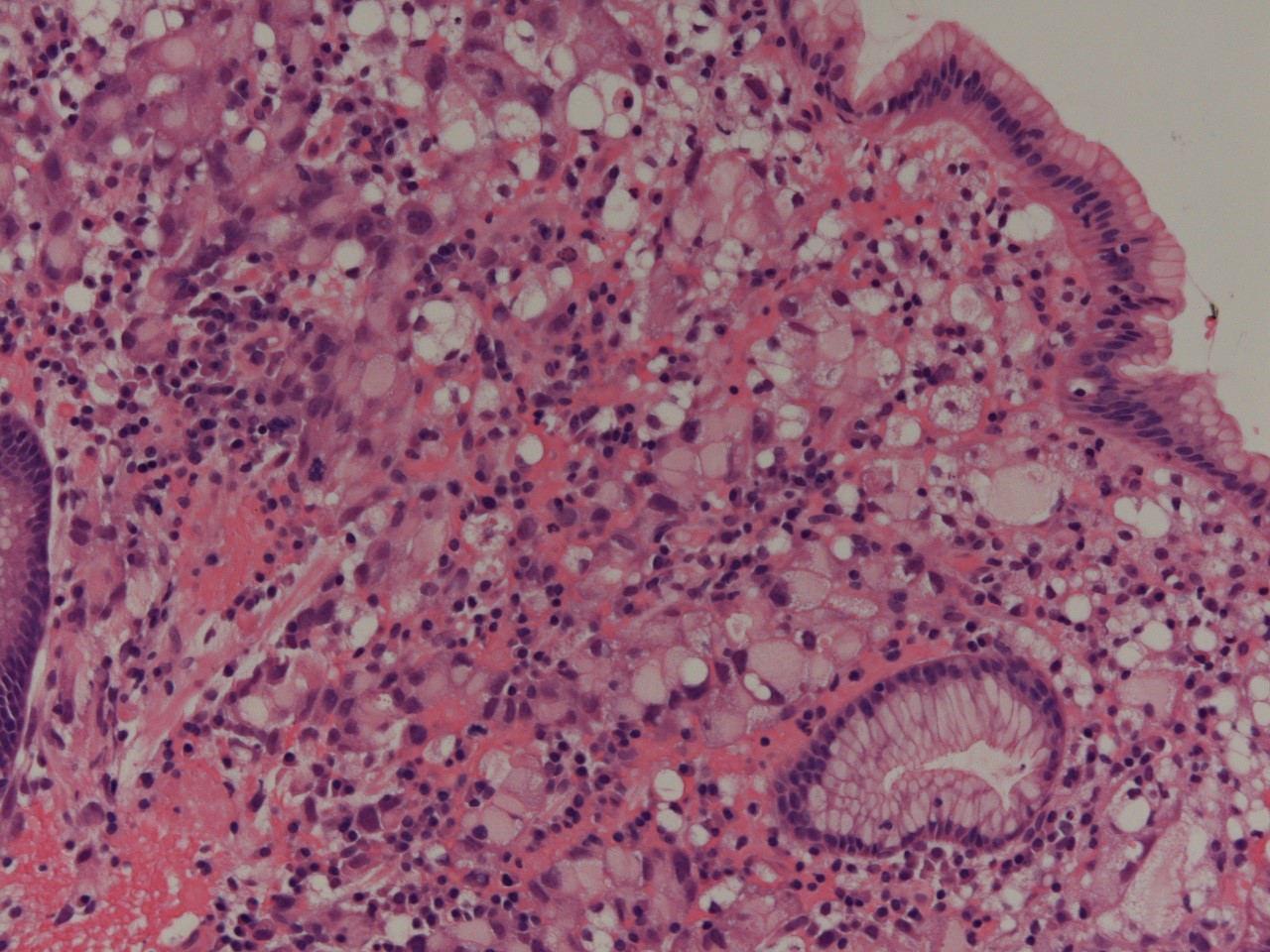

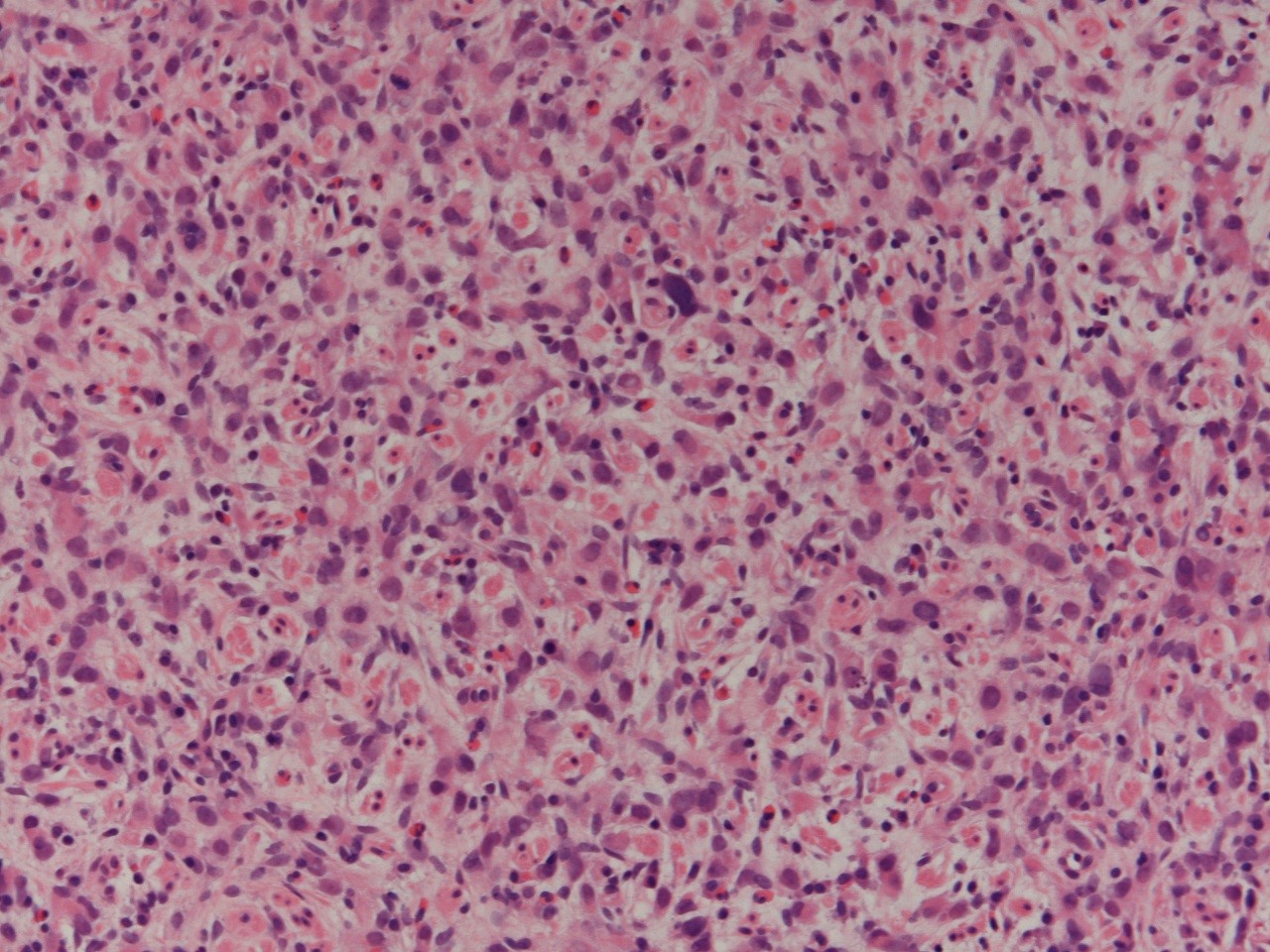

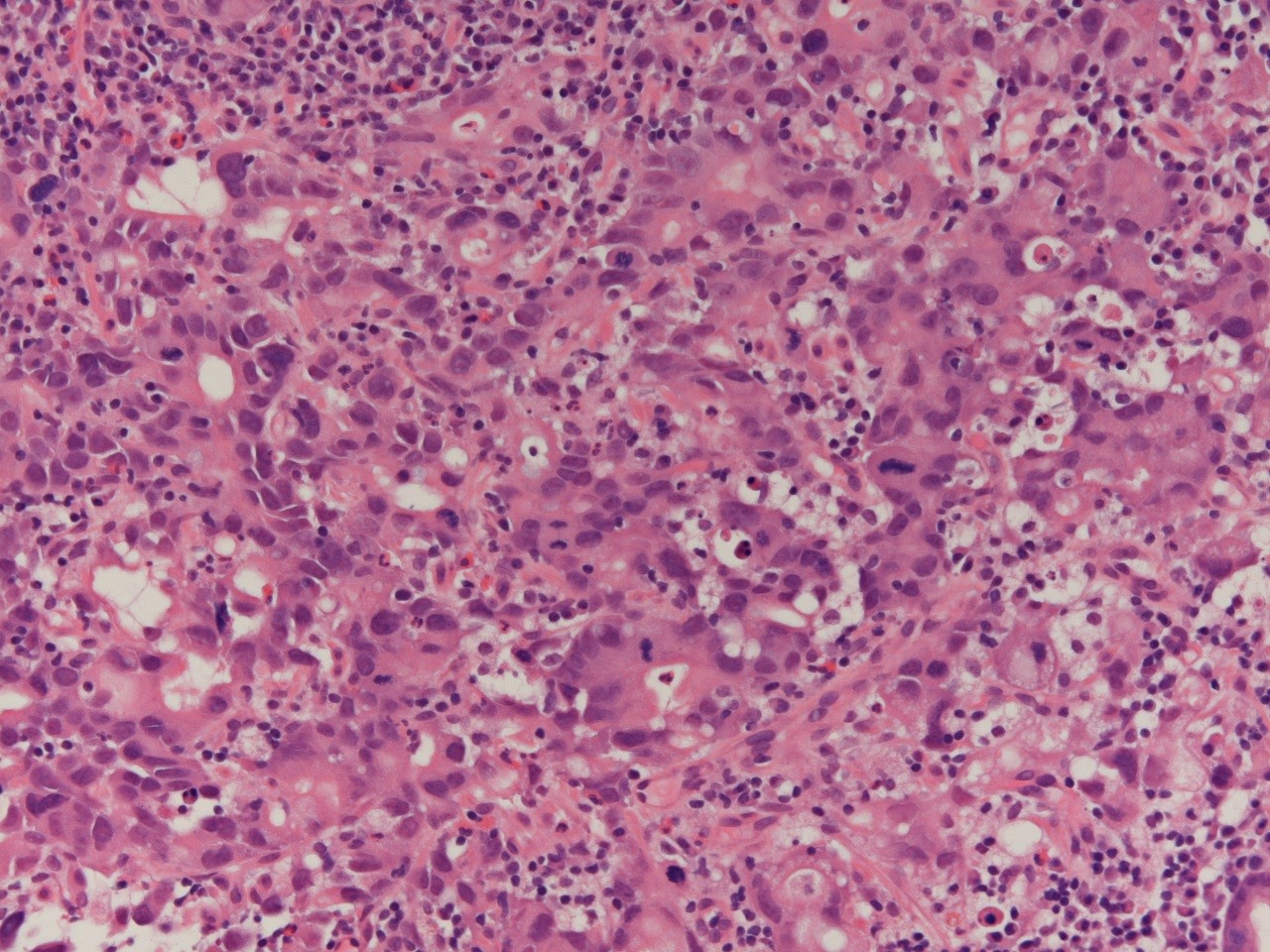

The adenocarcinoma can have two main types of microscopic pattern, intestinal and diffuse. The intestinal type exhibits easily identifiable glands and therefore tends to be well or moderately differentiated (the intestinal type can be subdivided into tubular, papillary and mucinous categories). The diffuse form is composed of sheets of markedly atypical cells that show little gland formation. The diffuse type often features signet ring cells. Diffuse type gastric adenocarcinomas can grow along the wall of the stomach and stiffen it to produce the 'leather bottle' stomach (linitis plastica); the alterations to the overlying gastric mucosa can be very limited.

|

|

|

|

A signet ring cell adenocarcinoma

|

Another region of the same tumour. This part of the tumour is undifferentiated.

|

A further region of the same tumour in which some gland formation is present.

|

The tumour can invade upwards into the oesophagus, although invasion in the direction of the flow of food into the duodenum is unusual. Direct invasion can also involve the transverse colon (possibly yielding a gastrocolic fistula), the spleen and the pancreas.

The metastases of gastric adenocarcinoma tend to involve the local lymph nodes, supraclavicular lymph nodes and the liver. The tumour can spread across the abdominal cavity (transcoelomic spread) to metastasise to the ovary (Krukenberg tumour), uterus and Pouch of Douglas.

Staging

Gastric adenocarcinoma is staged by the TNM system.

|

T1

|

invades lamina propria or submucosa

|

|

T2

|

invades muscularis propria (T2a) or subserosa (T2b)

|

|

T3

|

penetrates the serosa but does not invade adjacent organs

|

|

T4

|

directly invades other organs

|

|

N0

|

No lymph node metastases

|

|

N1

|

Metastases in 1 to 6 lymph nodes

|

|

N2

|

Metastases in 7 to 15 lymph nodes

|

|

N3

|

Metastases in 16 or more lymph nodes

|

|

M0

|

No distant metastases

|

|

M1

|

Distant metastases

|

Clinical Features

The presentation of gastric adenocarcinoma tends to be with non-specific symptoms such as indigestion, upper abdominal pain, nausea and vomiting, anorexia and fatigue. Haematemesis or malaena may occur. A tumour which occupies a large volume of the stomach or causes linitis plastica can lead to a bloating sensation after meals, or a feeling of being full up easily (early satiety).

The tumour is seldom palpable on examination of the abdomen and it may be one of the supraclavicular lymph node metastases that is noticed first.

Investigations

An upper GI endoscopy (oesophagogastroduodenectomy) with a biopsy is the mainstay of the diagnostic investigations. A barium meal can disclose a mass lesion but does not provide histopathological material.

A CT scan, possibily supplemented by MRI can delineate the extent of the tumour and is integral to the staging. If surgery is contemplated the patient may require a staging laparoscopy to confirm the imaging findings by direct visualisation.

A full blood count is usually performed due to the possibility of the patient being anaemic due to blood loss or other effects of the tumour. As with other malignant tumours measurement of the blood calcium is prudent to exclude hypercalcaemia. The urea and electrolytes and liver function tests are usually also performed.

Treatment

The five year survival rate of gastric adenocarcinoma is around 5-10% due to the tendency of the tumour to present at a late stage, by which point surgery is not curative and possibly not even feasible as a palliative procedure. Thus, most patients will receive palliative therapy which is often in the form of chemotherapy and/or radiotherapy. In some patients chemotherapy may be employed to reduce the stage and/or size of the tumour to a level that is amenable to surgery. Nevertheless, curative treatment is not possible in most patients.

Endoscopic resection is possible for very early stage tumours. This approach is more common in Japan where the much higher incidence of the tumour has resulted in close scrutiny of the population for the disease and therefore a better chance of detecting the carcinoma before it has reached a high stage.

Other Tumours

Various other tumours can affect the stomach. The commonest of these is non-Hodgkin lymphoma, which is usually of either the extranodal marginal zone type or diffuse large B cell lymphoma type. Rarer tumours include gastrointestinal stromal tumours, carcinoid tumours and leiomyosarcomas.

Fundic gland polyps are small benign lesions that feature dilated glands which are lined by specialised and non-specialised cells