Contents

Gallstones

Gallstones are solid bodies that are formed in the biliary system from the contents of the bile. They may be present in 10-20% of the population, although the majority of people who have gallstones are asymptomatic. Gallstones are more common in women and in older people. They can range in size from a grain of sand to several centimetres and may be single or multiple. Multiple gallstones are often faceted due to the stones jostling against each other.

Gallstone disease is sometimes referred to as cholelithiasis. The term choledocholithiasis pertains to gallstones in the common bile duct.

There are two main types of gallstones: cholesterol and pigment.

Cholesterol Gallstones

Cholesterol stones are composed primarily (70-80%) of cholesterol; the other constituents include calcium, bile acids, bilirubin, proteins and fatty acids. Many cholesterol gallstones are therefore actually more accurately classified as mixed stones because they are not composed only of pure cholesterol (some reserve the term mixed stone for those than contain between 20-70% cholesterol). The basic mechanism for their formation is supersaturation of the bile by cholesterol. The cholesterol can then precipitate out and form a stone, rather like school chemistry experiments that involved growing copper sulphate crystals.

Oestrogen increases the levels of cholesterol secretion in the bile by stimulating the uptake of lipoproteins by the liver. Thus, cholesterol gallstones are more common in women; the oral contraceptive pill may also increase the incidence of gallstones.

Obesity and a high fat diet can also increase the delivery of cholesterol to the biliary tree.

Conditions that reduce the quantity of bile acids also predispose to the formation of cholesterol gallstones: bile acids emulsify the cholesterol in the bile and keep it in solution. A reduction in the amount of bile acid occurs in disorders of the terminal ileum, such as Crohn's disease.

Cholesterol gallstones are also more likely to form if their is hypomotility of the gallbladder, as can occur in pregnancy or fasting.

Cholesterol gallstones are usually green, due to staining by the bile, but can be yellow or white, especially if the cholesterol content is very high. The cut surface is laminated. A pure cholesterol stone is yellow and floats in water.

Pigment Gallstones

Pigment gallstones are dominated by bilirubin. Calcium is also present. Cholesterol accounts for less than 20% of the stone.

Pigment stones tend to form in people who have haemolytic anaemia because this group of disorders increases the bilirubin load imposed upon the liver. Pigment gallstones can also develop in infections of the biliary tree and cirrhosis.

Pigment gallstones typically have a smaller average size than cholesterol gallstones and are very dark.

Clinical Features

Gallstones are only symptomatic in approximately 15% of people who have them. However, if they do play up they can cause a variety of conditions.

Empyema and mucocoele are both complications of obstruction of the gallbladder by a gallstone. In the former case there is co-existent acute inflammation and the gallbladder becomes distended by pus. In the latter the gallbladder does not suffer acute inflammation but instead fills with the mucin produced by its mucosa.

The development of either adenocarcinoma of the gallbladder or cholangiocarcinoma is rare.

Gallstone ileus is a very rare complication of gallstones that has almost passed into legend. Theoretically, a gallstone can burrow through the wall of the gallbladder and if the gallbladder is in contact with the small or large bowel at this time the attendant inflammation can result in adhesions and the formation of a fistula. The gallstone passes through the fistula into the lumen of the bowel. For reasons that are not entirely clear the bowel can sometimes become thrown by the arrival of the gallstone and suffer paralysis of its peristalsis (ileus), which presents as bowel obstruction.

|

|

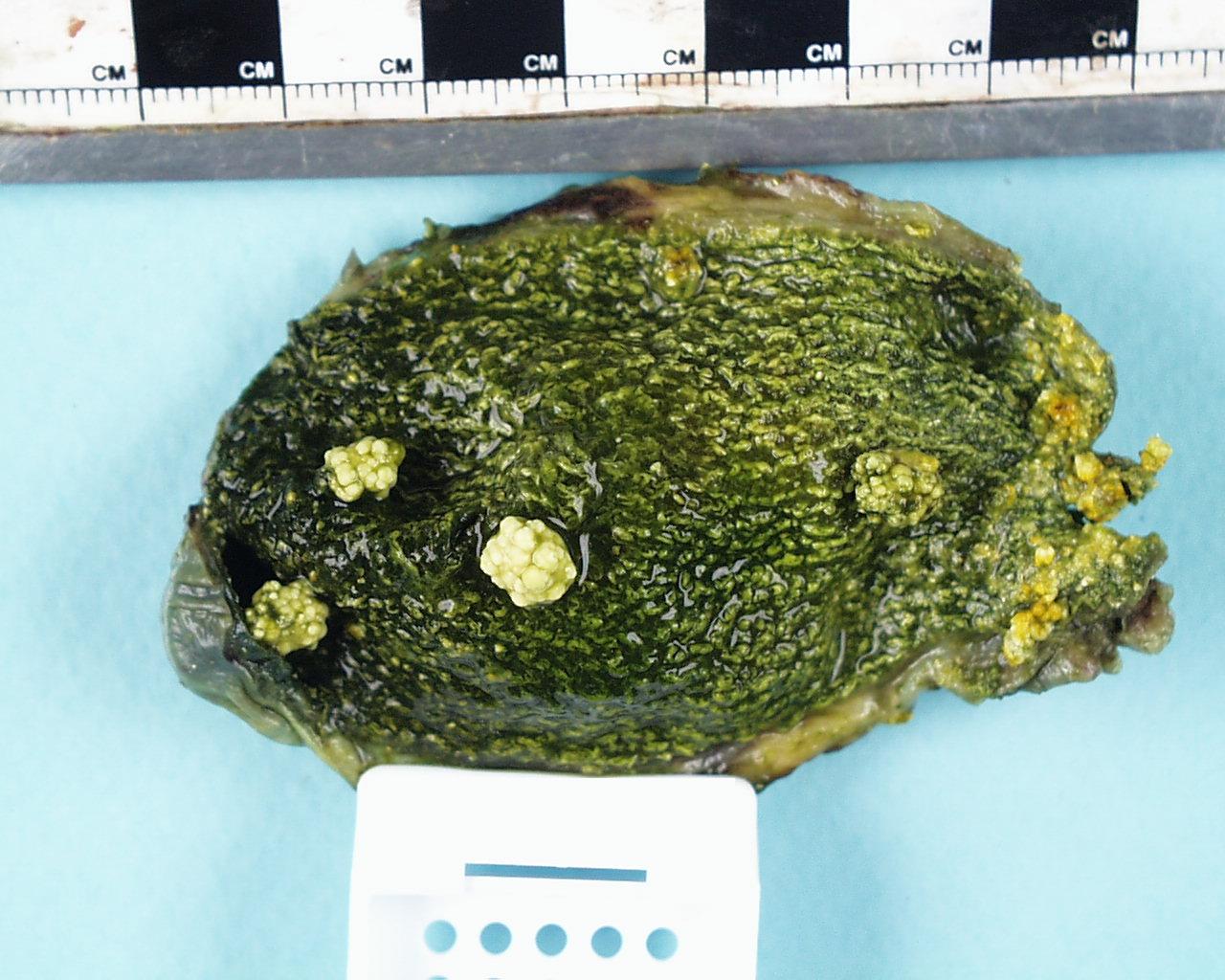

An opened gallbladder that is filled with numerous faceted gallstones

|

Acute Cholecystitis

Acute cholecystitis tends to occur in females between 20 and 40 years of age, although both genders can be affected and the age range is wide. In most cases there is obstruction of the neck of the gallbladder by a gallstone. The gallbladder becomes distended and acutely inflamed. Secondary infection can develop.

Acute cholecystitis can arise in the absence of an obstructing stone (acalculous cholecystitis) if there is some other form of obstruction of the gallbladder (such as a tumour), infection elsewhere in the biliary tree, torsion of the gallbladder or vasculitis.

Pathology

The pathology of acute cholecystitis is centred around the mechanisms of

acute inflammation. Thus, the gallbladder exhibits an infiltrate of neutrophils and shows oedema and hyperaemia, resulting in swelling of the wall. The mucosa can undergo necrosis and if the condition progresses there can be intramural abscesses and necrosis. If the episode still fails to resolve the gallbladder can fill with pus and an empyema can arise. Perforation can occur. Peritonitis may develop.

The condition tends to resolve if the gallbladder manages to shove the stone out of the way.

Clinical Features

Acute cholecystitis presents with severe pain in the right hypochondrium and the epigastrium. The pain is continuous and may radiate to the back, scapula or shoulder. If the disease progresses the pain becomes generalised to the whole abdomen as a consequence of the onset of peritonitis. There is often associated nausea and vomiting. Fever is often present. Some patients can be jaundiced.

The patient is tender in the right upper quandrant and may exhibit guarding and rebound tenderness. The pain is worse on deep inspiration and may cause inspiration to be halted. The distended gallbladder is claimed to be palpable in 25-50% of patients.

Chronic Cholecystitis

Chronic cholecystitis is a more long term, grumbling form of inflammation of the gallbladder that may be due to mechanical irritation of the gallbladder by the gallstones rattling around in it, or by repeated episodes of either acute cholecystitis or subclinical acute cholecystitis. It is more common in women and the overweight.

Cholesterolosis is the name applied to the presence of aggregates of foamy macrophages in the mucosa of the gallbladder. The macrophages contain cholesterol. The mucosa of the gallbladder may have multiple yellow flecks that can be seen macroscopically. In some cases the chosterolosis may be sufficient to cause the mucosa to form polypoid projections.

|

|

|

An opened gallbladder that contains a few small cholesterol gallstones and also exhibits the yellow flecked mucosa of cholesterolosis.

|

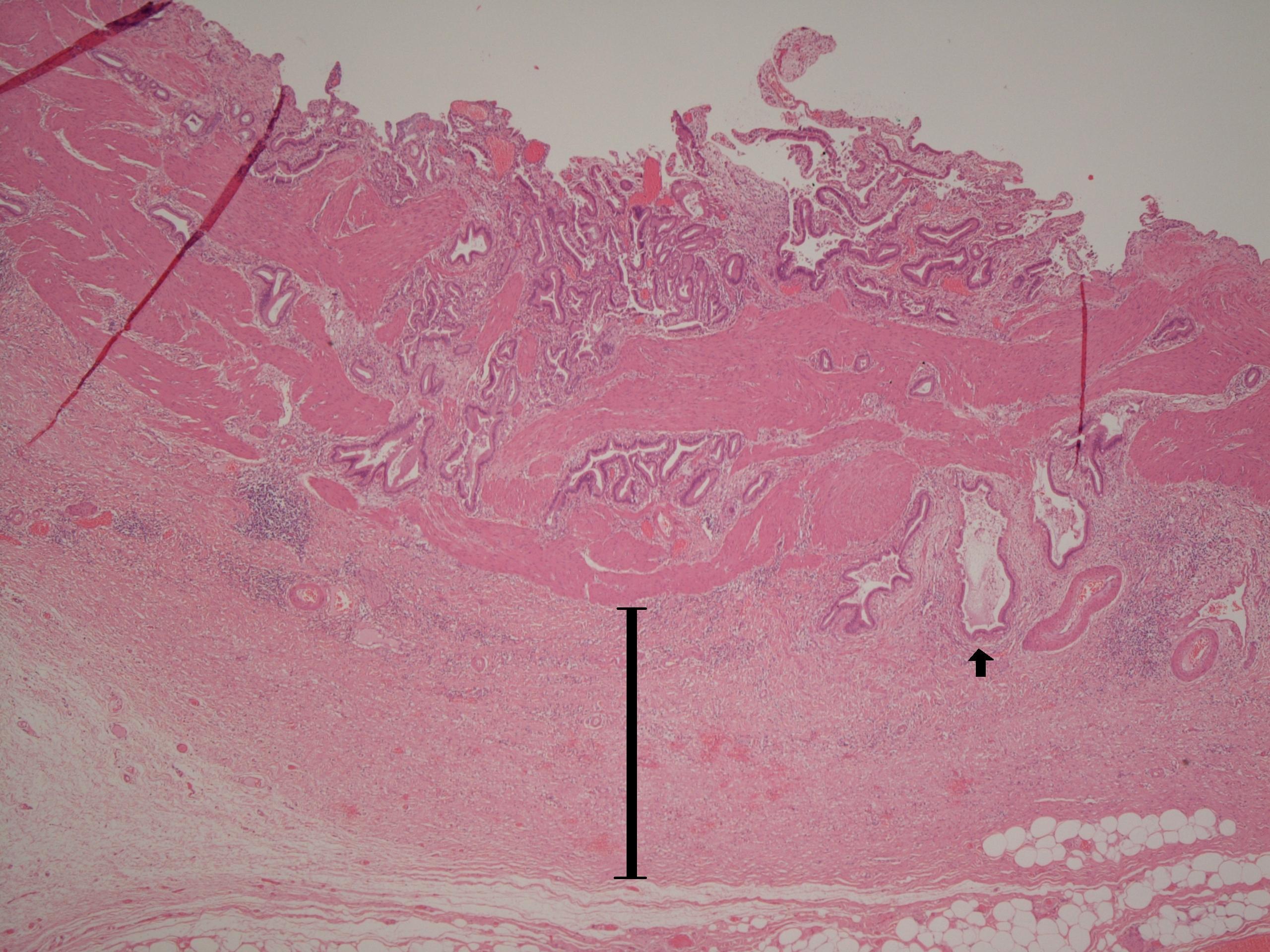

A microscopic image of the wall of a gallbladder that shows chronic cholecystitis. A Rokitansky-Aschoff sinus is indicated by the arrow. The bar denotes fibrosis.

|

Pathology

The wall of the gallbladder is thickened, fibrotic and displays hypertrophy of the smooth muscle. Despite the fibrosis and muscle hypertrophy, the gallbladder can be smaller than usual. Downbuds of the mucosa can protrude through the muscularis propria and are known as Rokitansky-Aschoff sinuses. Bile may accumulate in these sinuses and if rupture occurs a granulomatous / foreign body response to the bile can occur. An infiltrate of chronic inflammatory cells may be present even in the absence of rupture of a sinus.

A porcelain gallbladder is a rare variant of chronic cholecystitis in which the fibrotic gallbladder has undergone considerable calcification.

Clinical Features

The patient suffers from episodes of pain in the right upper quadrant. The pain may be precipitated by meals, particularly fatty meals. As with acute cholecystitis the pain can radiate to the back. Nausea and vomiting may accompany the pain.

Biliary Colic

Biliary colic shares similarities with acute cholecystitis but is due to obstruction of the common bile duct, not the neck of the gallbladder, by a gallstone. The clinical presentation resembles acute cholecystitis, although fever is said not to be found. Biliary colic tends to resolve spontaneously within twenty-four hours once the biliary tree has managed to squeeze the stone out into the duodenum.

Ascending Cholangitis

Ascending cholangitis is a bacterial infection of the biliary tree that usually only occurs if the biliary system is obstructed by gallstones (or rarely another lesion). The bacteria are typically Gram negative bacilli.

The presentation resembles acute cholecystitis and biliary colic, with an emphasis on the combination of fever and jaundice. Septicaemia can develop and be life-threatening.

Investigations

Demonstration of gallstones is best accomplished by ultrasound. Only around 10% of gallstones are radio-opaque and therefore most gallstones do not show up on a plain abdominal X-ray. Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) or percutaneous transhepatic cholangiopancreatography are only rarely required (although become more important in the case of gallstones in the common bile duct).

Liver function tests should be performed to determine if the biliary problems have impacted on the liver.

Other blood tests, such as a full blood count, urea and electrolytes, are carried out as part of a more general evaluation of the presentation, rather than for specific diagnostic purposes.

Treatment

Cholecystectomy is the mainstay of treatment for symptomatic gallstone disease. The excision of the gallbladder removes the main site in which stones can form. It is used to treat chronic cholecystitis and to prevent repeat episodes of biliary colic or acute cholecystitis. Incidentally discovered gallstones may be treated by cholecystectomy if there is high chance of future complications developing, especially if the patient is not well placed to tolerate those complications.

Unless the gallbladder is gangrenous or perforated, cholecystecomy is often avoided during acute cholecystitis and biliary colic. Instead the patient is given analgesia, intravenous fluids, often antibiotics and is kept nil by mouth. The acute episode will usually resolve in a few days with this conservative management, although the gallbladder is typically then living on borrowed time and will be excised within the next couple of months, if not sooner.

Ascending cholangitis requires aggressive treatment with antibiotics and prompt relief of the blockage to the biliary system once the patient has been stabilised.

It may be possible to remove a common bile duct stone by ERCP; this frequently requires an incision to be made in the sphincter of Oddi (sphincterotomy).

Medical treatment can be attempted. Chenodeoxycholic acid or ursodeoxycholic acid can be given orally in an attempt to dissolve the gallstones. Extracorporeal shockwave lithotripsy aims to break up stones by bombarding them with high frequency sound waves. Both treatments may deal with existing stones but do not address the problems of recurrence.