Contents

Introduction

Gastro-oesophageal reflux disease is a common condition in which the function of the lower oesophageal sphincter is defective. This permits the acidic gastric contents to squirt back into the oesophagus where they can damage the oesophageal mucosa. Various factors can predispose to the development of gastro-oesophageal reflux disease.

- Obesity

- Smoking

- Pregnancy

- Hiatus hernia

- Smooth muscle-relaxing drugs

- Surgery

- Balloon dilatation of the lower oesophagus

Gastro-oesophageal reflux disease tends to affect middle aged to older people and can have a female predominance.

Hiatus Hernia

A hiatus hernia is a protrusion of part of the stomach through the oesophageal opening (hiatus) in the diaphragm. Hiatus hernias are found in many people who have gastro-oesophageal reflux disease. There are two types of hiatus hernia, sliding and rolling.

The sliding form accounts for 90% of hiatus hernias. The gastro-oesophageal junction slips through the oesophageal opening in the diaphragm such that the gastro-oesophageal junction is contained within the thorax.

The rolling type of hiatus hernia occurs when part of the fundus of the stomach protrudes up through the oesophageal opening in the diaphragm and lies alongside the gastro-oesophageal junction and the lower part of the oesophagus.

|

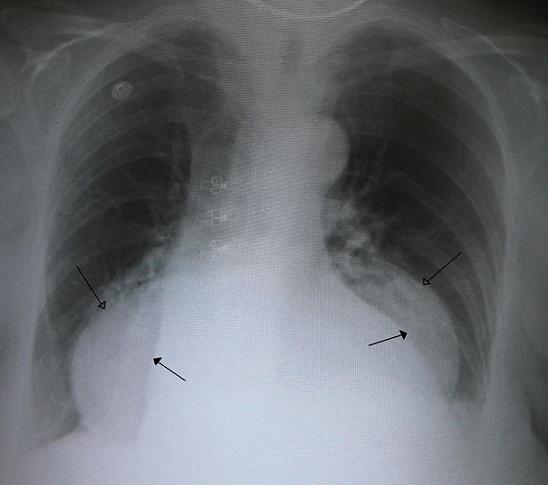

This chest X-ray shows a hiatus hernia (hollow headed arrows); the edges of the heart are indicated by the solid headed arrows

Image courtesy of Wikipedia

|

Both types of hiatus hernia interfere with the normal sphincter mechanism at the gastro-oesophageal junction and therefore make reflux of gastric acid into the oesophagus more likely. The hernia is usually small but in a few cases most of the stomach may end up in the thorax.

As with other types of hernia incarceration and strangulation of a hiatus hernia can occur, although are unusual.

Barrett's Oesophagus

Barrett's oesophagus is a form of

metaplasia that is considered to be a response of the oesophagus to chronic bombardment with gastric acid in gastro-oesophageal reflux disease. Although stratified squamous mucosa is usually an effective, resilient barrier it is not ideally suited to resist gastric acid. By mechanisms that are not entirely clear the repeated damage to the squamous mucosa of the oesophagus by gastrc acid induces a change from squamous mucosa to glandular mucosa (the stomach itself is lined by glandular mucosa which secretes mucus which protects the stomach against its own acid; the small bowel also adopts a similar strategy). The characteristic feature of the glandular mucosa in Barrett's oesophagus is that it manifests intestinal metaplasia, either in the form of scattered goblet cells or a fully developed villiform surface and numerous goblet cells. The mucosa may also resemble either the specialised or non-specialised mucosa of the stomach, with superadded intestinal metaplasia, or may be closer to small bowel mucosa, or may just be glandular mucosa that has no convincing normal analogue.

Much angst has been expended over exactly what is necessary to be seen in a biopsy for a definitive histpathological diagnosis of Barrett's oesophagus to be rendered and what words should be applied to biopsies that fall short of this but still have glandular mucosa. For a definitive diagnosis of Barrett's oesophagus to be made histopathologically the biopsy must demonstrate glandular mucosa that exhibits intestinal metaplasia and also includes a native oesophageal duct and/or gland. This presence of the oesophageal duct/gland means that the biopsy was definitely from the oesophagus and that this fact can be asserted by histopathological examination. If the native oesophageal duct/gland is not observed then it cannot be proven histopathologically that the biopsy is from the oesophagus, a fact that is important given that Barrett's oesophagus often co-exists with a hiatus hernia distal to it, where the hiatus hernia can confuse the evaluation of the endoscopic anatomy: in such cases, even if all the other features of Barrett's oesophagus are present, the inference that the biopsy represents Barrett's oesophagus is dependent on the statement supplied by the endoscopist that the biopsy is definitely from the oesophagus.

Regardless of what tribulations are endured in the wording of the histopathology report, it should be remembered that glandular mucosa looks quite different from squamous mucosa endoscopically and therefore credit should be given to the endoscopist for knowing what they are doing (with the caveat that a sliding hiatus hernia can confuse the situation). Therefore, the most important aspect of the biopsy report is not necessarily which form of various equivalent phrases is used to convey that glandular mucosa is contained in a biopsy that the endoscopy says was taken from the oesophagus, but whether or not dysplasia or malignancy is identified in that biopsy.

|

|

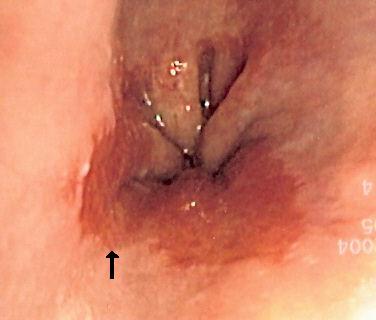

Endoscopic image of Barrett's oesophagus

The redder mucosa, indicated by the arrow, is the Barrett's oesophagus

Image courtesy of Wikipedia

|

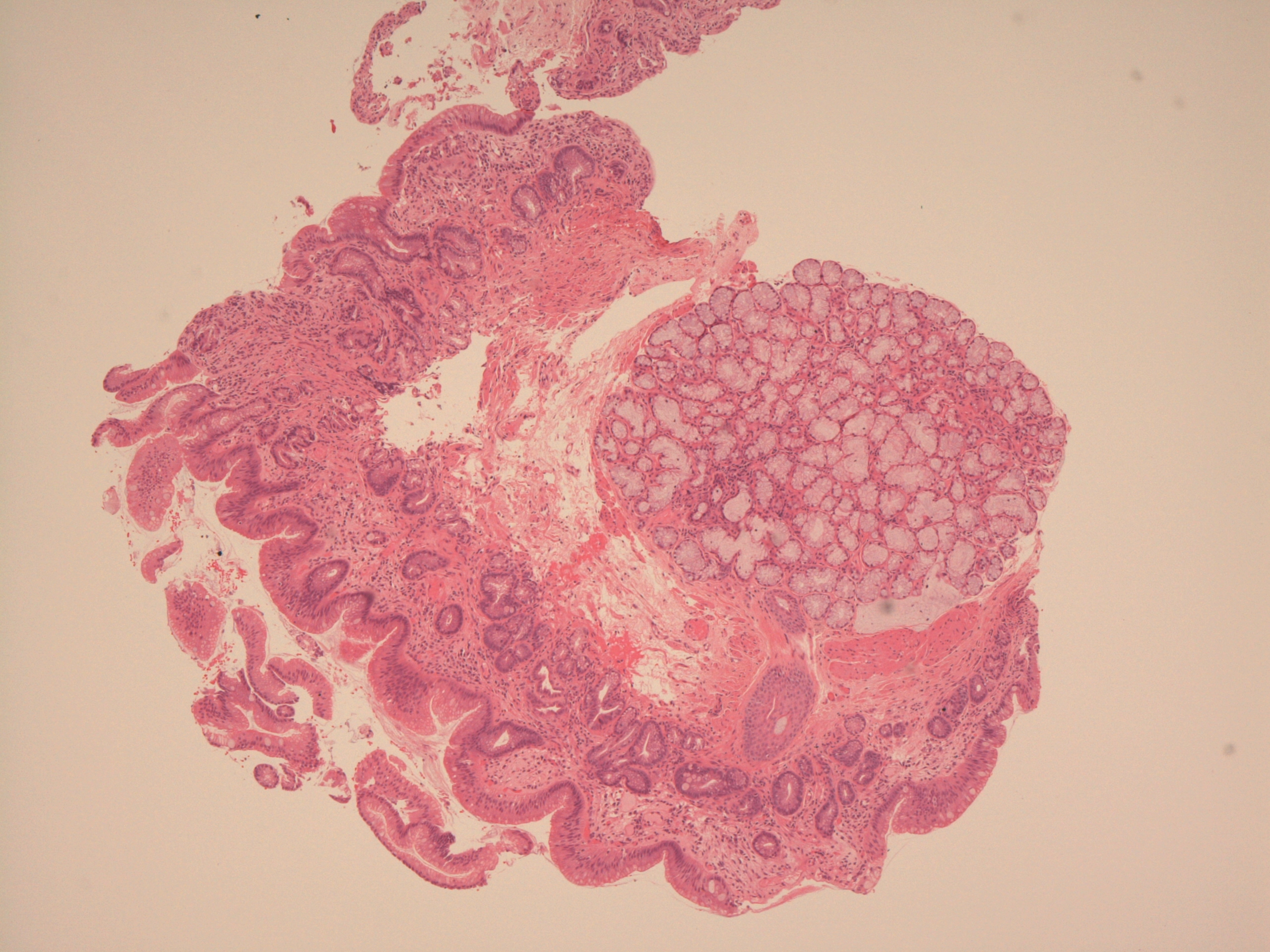

Microscopic image that is diagnostic of Barrett's oesophagus

A native oesophageal gland and duct is present

|

|

|

|

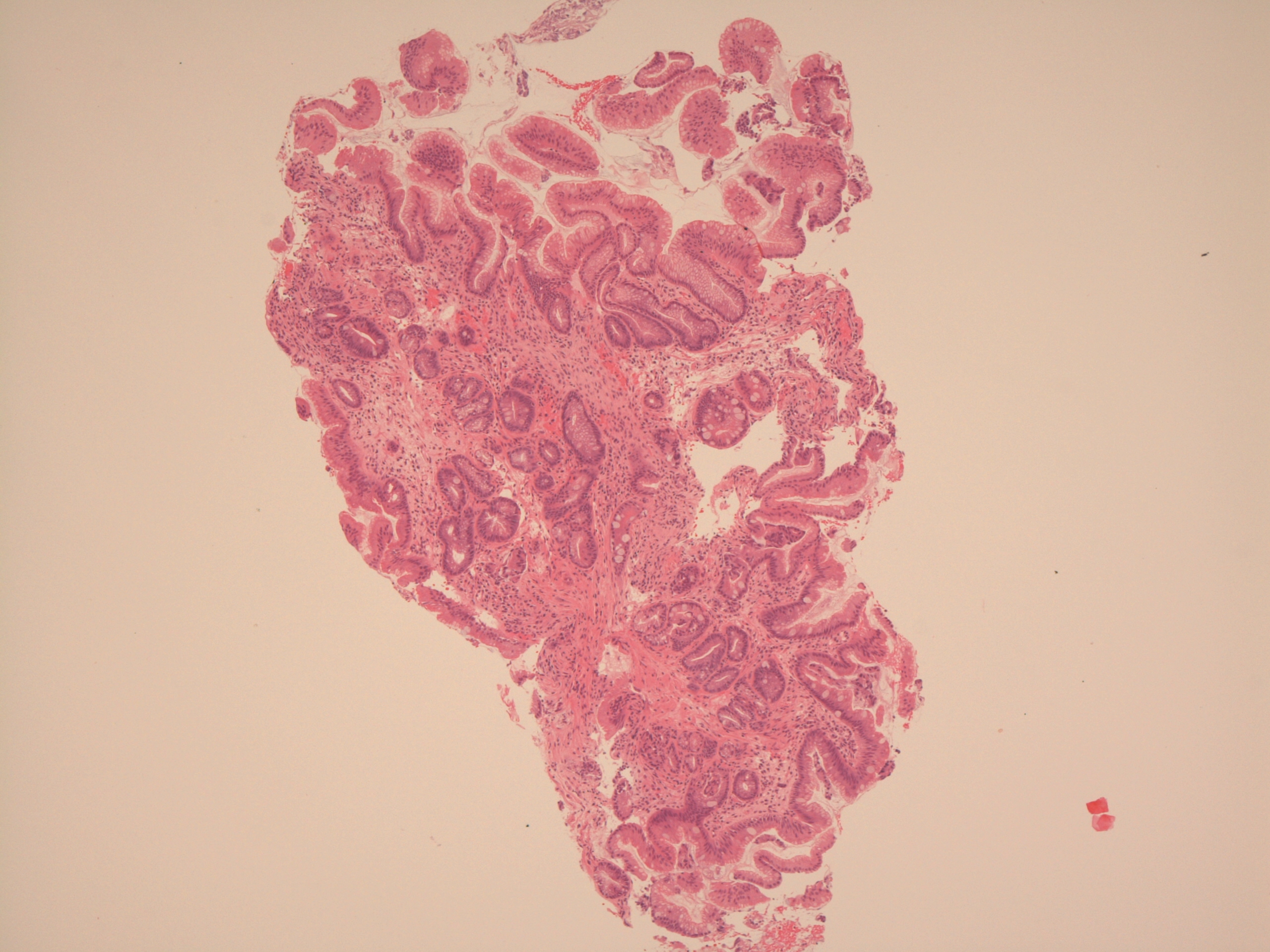

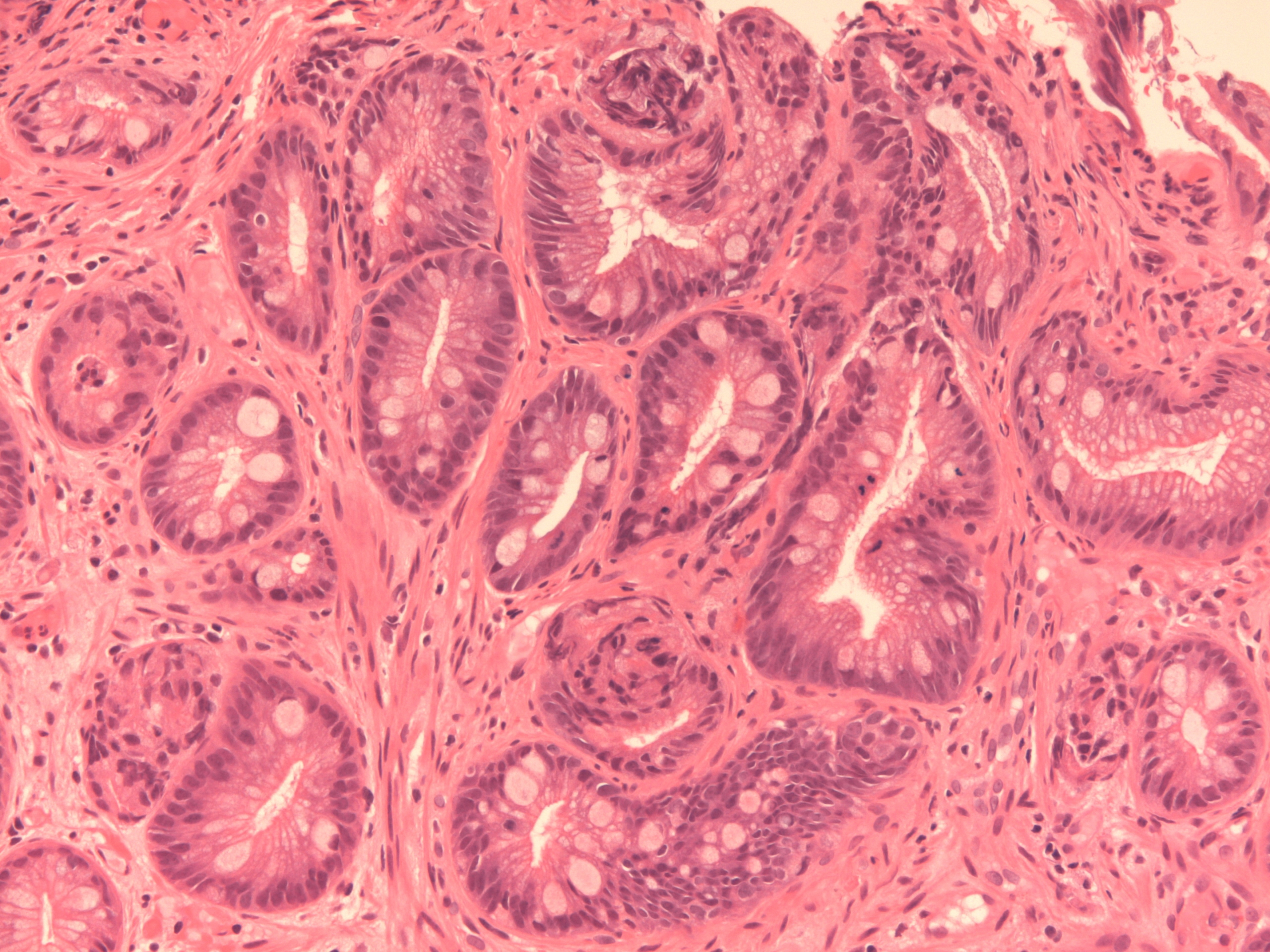

A more typical microscopic image of Barrett's oesophagus that shows glandular mucosa and intestinal metaplasia

|

Higher power image of intestinal metaplasia

|

The development of Barrett's oesophagus indicates that the mucosa of the oesophagus has started to alter the expression of its DNA and thus has potentially made preparations to become neoplastic, albeit that metaplasia alone is not a form of neoplasia. Further repeated injury by acid, coupled with numerous cycles of cell regeneration and turnover of DNA, predispose to the generation of mutations which can lead to dysplasia of the glandular mucosa and ultimately to adenocarcinoma.

The terms short segment and ultrashort segment are sometimes applied by the endoscopist to oesophaguses in which the glandular mucosa only extends for a short, or very short distance beyond the gastro-oesophageal junction. Biopsy of these cases can be unrewarding simply because of the proximity to the gastro-oesophageal junction and its native glandular mucosa.

Clinical Features

Gastro-oesophageal reflux disease presents with retrosternal chest pain that is usually burning in character. The pain does not normally radiate to the jaw or arm but the distinction from the pain of angina or a myocardial infarction is not always as easy as might be expected.

The pain is precipitated by meals (when the stomach goes to work and churns) and is worse on lying down, bending over or straining. Antacids relieve the pain. Rarely, the pain is induced by exercise.

Some patients may experience the sensation of acid or bile regurgitating into their mouth (apparently known as waterbrash).

Investigations

In many cases the clinical presentation may be sufficiently characteristic to the extent that investigations are superfluous. However, if dysphagia is present then this may need further evaluation.

Treatment

Simple measures such as raising the head of the bed and eating smaller meals can be effective. Any predispoing factors such as smoking, obesity and drugs may be amenable to modification. Antacids can relieve the pain of the reflux. Proton pump inhibitors suppress the secretion of acid by the stomach and can therefore prevent the symptoms.

Surgery is possible for a hiatus hernia. The Nissen fundoplication wraps part of the fundus of the stomach around the gastro-oesophageal junction to stop it from sliding back up through the oesophageal opening in the diaphragm.

Patients who have Barrett's oesophagus may undergo endoscopic surveillance, especially if dysplasia is present. It is estimated that approximately 50% of patients who have high grade dysplasia in a biopsy of Barrett's oesophagus will actually have a co-existing adenocarcinoma somewhere nearby in the oesophagus and these patients require treatment. Local resection or laser ablation of the abnormal mucosa can be attempted in Barrett's oesophagus in some cases.