Contents

Bronchial Carcinoma

Bronchial carcinoma is more commonly known as lung cancer. It is the commonest cancer in men and competes with breast carcinoma to be the commonest cancer in women. The incidence is approximately 75 per 100,000 per year. The incidence in women is rising and this is affecting the traditional skew towards males of the male : female ratio. The age of onset is usually in the seventh and eighth decades. Lung cancer is one of the commonest cancers worldwide.

The main aetiological factor is cigarette smoking which accounts for over 90% of cases. Other risk factors include radon gas (found in granite rich areas), asbestos, arsenic, tars, soot and nickel.

The elevated risk of lung cancer caused by cigarette smoking takes about 15 years to subside after the cessation of smoking.

Pathology

Bronchial carcinoma tends to develop in the main bronchus or one of the lobar bronchi and is thus located centrally. A minority of tumours arise in the periphery.

The tumour can be an ulcerated, sessile plaque or a more exophytic, nodular lesion; in both cases there is invasion of the underlying lung. Both patterns also narrow the lumen of the affected bronchus. This impairs drainage and ventilation of the affected lobe of the lung, leading to pneumonia or collapse of the lung distal to the tumour. The tumour may undergo cavitation.

Bronchial carcinomas have a variety of structures and organs they can invade directly. Centrally positioned tumours may infiltrate the left recurrent laryngeal nerve, the phrenic nerve, the oesophagus and the pericardium. The superior vena cava can be compressed or invaded. Peripherally situated tumours or large central tumours can reach the pleural and cause a pleural effusion.

Tumours at the apex of the lung can invade upwards into the lower part of the brachial plexus. This is known as a Pancoast tumour. The patient presents with a unilateral Horner's syndrome and sensorimotor defects in the C8 and T1 distributions in the ipsilateral arm.

|

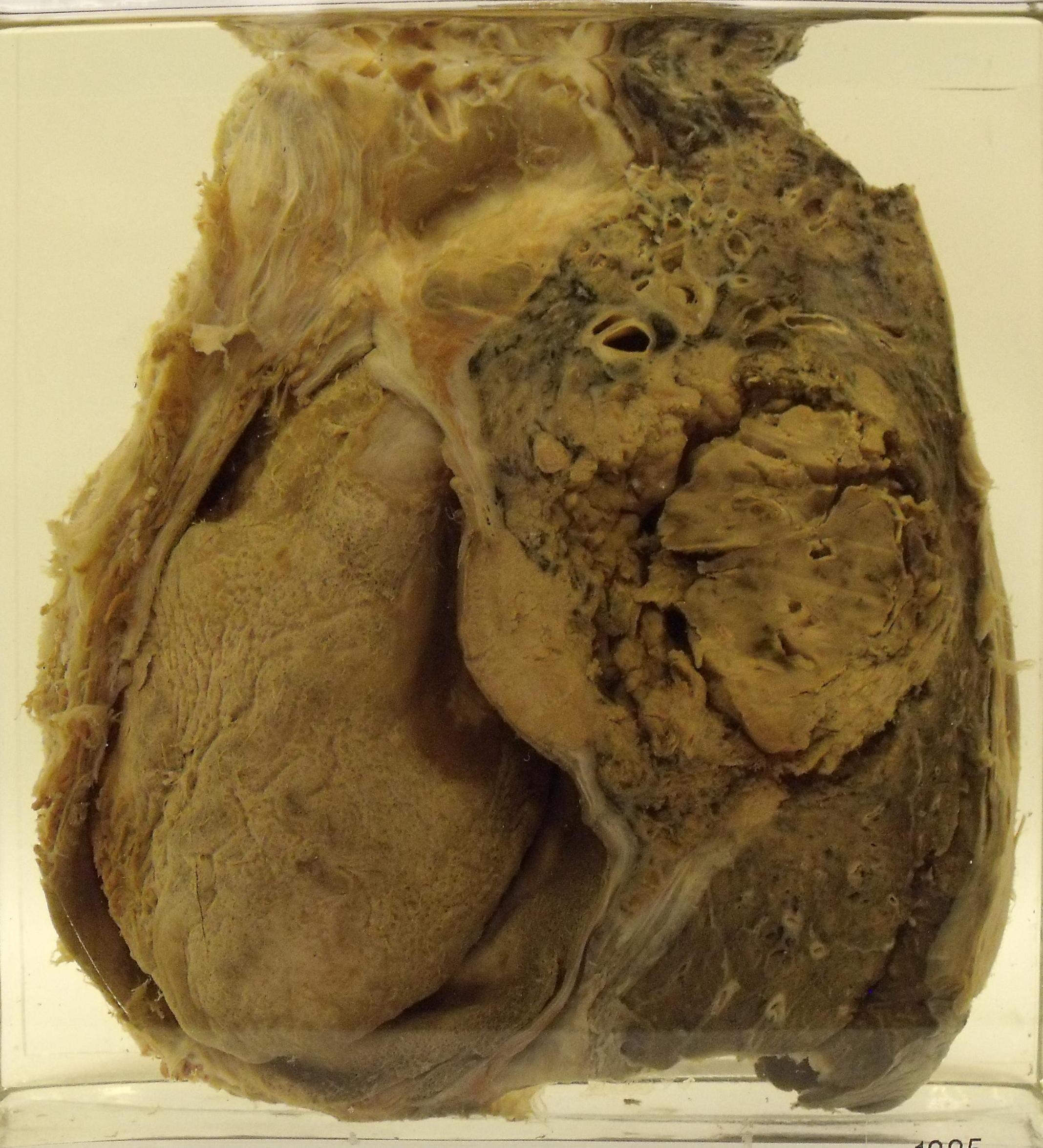

This bronchial carcinoma has arisen in the left lung and is chomping into the pericardium

Image courtesy of Dr Carol Shiels

|

Lymphatic spread is to the bronchial and hilar lymph nodes. The supraclavicular lymph nodes are also often involved. The lymphatic spread can also be retrograde; this pattern can permeate the lymphatics just beneath the pleura to yield a fine network of white, infiltrated lymphatics that is known as lymphangitis carcinomatosa.

Distant metastases can affect a variety of organs but the bone, liver, brain and adrenal gland are among the more preferred destinations for the tumour. Bronchial carcinoma often does not waste time in metastasising and can do so early in the life of the tumour.

The main microscopic distinction is between small cell carcinoma and non-small cell carcinoma. This classification has important treatment implications. The main subtypes of non-small cell carcinoma are squamous cell carcinoma, adenocarcinoma and large cell (large cell neuroendocrine) carcinoma.

Squamous cell carcinoma and small cell carcinoma each account for 30-40% of bronchial carcinomas. Primary adenocarcinomas contribute 15-30% while large cell carcinomas weigh in with around 10%. Other, rarer types exist.

Squamous cell carcinomas and adenocarcinomas of the lung follow the same basic patterns are those of other organs. Squamous cell carcinomas are particularly likely to cavitate. Adenocarcinomas are more likely than the other subtypes to be situated peripherally. Given that the lungs are a common site for metastases it is important to distinguish a primary lung adenocarcinoma from a secondary; immunohistochemistry can be very helpful in this instance due to the characteristic CK7 positive, CK20 negative, TTF-1 positive, napsin-A positive pattern of primary lung adenocarcinomas.

Bronchoalveolar adenocarcinoma is an unusual variant of primary bronchial adenocarcinoma in which the tumour cells tend to grow along the lining of the alveoli and the airways.

Small cell carcinomas can actually affect a wide variety of organs but are most commonly seen in the lung. They are derived from neuroendocrine cells of the mucosa and are composed of hyperchromatic cells which possess a high nuclear : cytoplasmic ratio. Nucleolation is unusual and the cells instead possess a granular pattern of chromatin that for better or worse has the term 'salt and pepper' inextricably appended to it. The cells are closely packed and because they are quite soft they indent each other in a process known as moulding. Small cell carcinomas are prone to crush artefact. DNA can also leak out from the cells and line blood vessels (Azzopardi effect).

The neuroendocrine origin of small cell carcinomas means that they are well equipped to secrete a variety of hormonally active substances and induce

paraneoplastic phenomena.

Clinical Features

Bronchial carcinoma can present with a persistent cough (which may or may not be productive) and haemoptysis. Dyspnoea can arise, either from pneumonia or collapse of a lobe or whole lung.

The tumour may cause a pleural effusion and this may be the initial finding.

A hoarse voice can result from invasion of the left recurrent laryngeal nerve.

Infiltration of the phrenic nerve can cause paralysis of the ipsilateral hemidiaphragm. This may either produce dyspnoea or be discovered on a chest X-ray taken for another reason.

Invasion or compression of the oesophagus yields

dysphagia.

Involvement of the superior vena cava causes the superior vena cava syndrome in which the patient has a swollen, oedematous head and arms, coupled with distended superficial veins on the upper chest.

Extension of the tumour into the pericardium produces a pleural effusion. Atrial fibrillation can develop.

Pancoast tumours cause neurological symptoms in the C8 and T1 distributions, together with an ipsilateral Horner's syndrome.

Patients may exhibit clubbing.

Paraneoplastic Phenomena

The wide array of paraneoplastic phenomeona which are associated with bronchial carcinoma are largely the responsibility of the small cell variant. However, the commonest one, hypercalcaemia, is actually more frequently associated with squamous cell carcinoma.

Cushing's syndrome is probably the most well known of the paraneoplastic phenomena of bronchial carcinoma and is caused by the secretion of ACTH by a small cell carcinoma. Other paraneoplastic phenomena are listed below.

- SIADH

- Eaton-Lambert syndrome

- Dermatomyositis

- Cerebellar degeneration

- Peripheral neuropathy

- Hyperthryoidism

- Migratory thrombophlebitis

- Acanthosis nigricans

Staging

Bronchial carcinoma is staged by the TNM system.

|

T1a

|

Tumour less than 20mm in maximum dimension

|

|

T1b

|

Tumour more than 20mm but less than 30mm in maximum dimension

|

|

T2a

|

Tumour more than 30mm but less than 50mm in greatest dimension

Tumour of any size that is within 20mm of the carina, or involves the visceral pleura or is associated with atelectasis or obstructive pneumonitis that reaches the hilum but does not involve the entire lung

|

|

T2b

|

Tumour more than 50mm but less than 70mm in greatest dimension

|

|

T3

|

Tumour more than 70mm in maximum dimension or tumour of any size that invades the parietal pleura, mediastinal pleura, chest wall, diaphragm or pericardium or is in the main bronchus and is less than 20mm from the carina, or is associated with atelectasis or obstructive pneumonitis that reaches the hilum and involves the entire lung

|

|

T4

|

Tumour of any size that invades the mediastinum, heart, great vessels, recurrent laryngeal nerve, oesophagus, vertebral body or carina or has separate nodules in the ipsilateral lung

|

|

N0

|

No lymph node metastases

|

|

N1

|

Metastases in ipsilateral intrapulmonary, peribronchial or hilar lymph nodes

|

|

N2

|

Metastases in ipsilateral mediastinal or subcarinal lymph nodes

|

|

N3

|

Metastases in contralateral peribronchial, hilar or mediastinal lymph nodes or any supraclavicular or scalene lymph nodes

|

|

M0

|

No distant metastases

|

|

M1a

|

Separate tumour nodules in a contralateral lung lobe and pleural nodules or a malignant pleural or pericardial effusion

|

|

M1b

|

Distant metastases

|

Cut Up

The cut up of a lung specimen follows the

solid organ model, although strictly speaking the lung is not solid. Furthermore the presence of the bronchus at the resection margin makes the analogy closer to a lollipop.

The particular nuances that relate to a lobectomy or pneumonectomy specimen concern the hilar region and the pleural surfaces. The cut ends of the bronchus and the hilar blood vessels are surgical margins and should be sampled en face. In addition, the specimen is usually not divided into multiple slices but instead may be bisected through the tumour in a vertical plane or possibily divided into only a few slices.

The pleural surface is not a margin but nevertheless the distance of the tumour to the superior, inferior, anterior, posterior and lateral pleural surfaces should be measured. The medial aspect of the specimen may have a pleural aspect and a non-pleural aspect. The non-pleural aspect is a margin and may be referred to as the mediastinal margin; the distance to the medial part of the specimen should also be documented, as should that to the vascular and bronchial margins.

The blocks are taken to demonstrate the tumour and the closest pleural surfaces. Most of the tumours are close to the hilar aspect so at least one of these blocks will include the medial margin.

The relationship of the tumour to the fissure(s) should be noted in a lobectomy specimen.

The hilum should be inspected for lymph nodes and these embedded.

It is not unusual for the background lung to display consolidation and this should be sampled. A background block of non-involved lung should also be taken.

Opinion is divided as to whether the lung should be bisected when it is received or instead inflated with formalin. Inflation is accomplished by injecting formalin into the bronchus and has the advantage of giving the specimen a more anatomically familiar shape. The margin distances may be larger in an inflated specimen.

Investigations

The standard approach for investigating a tumour applies. The simplest way to obtain a histocytopathological diagnosis is sputum cytology. This can be positive in a siginificant number of patients and if the radiological studies are robust may save the need for a more invasive procedure.

Despite the merits of sputum cytology most patients will undergo a bronchoscopy. Centrally located tumours may be biopsied directly; bronchial washings can supplement the biopsy. More peripherally located tumours may require a brochoalveolar lavage to attempt to flush out some cells shed by the tumour.

If bronchoscopy fails to yield a diagnostic sample, a CT guided core biopsy can be attempted.

Sampling of pleural fluid or a pleural biopsy may obviate the need for more invasive procedures if a pleural effusion is present.

Lung function tests are often undertaken because most of the patients are smokers and many of them will have

COPD that could impact on what treatment options are viable.

|

|

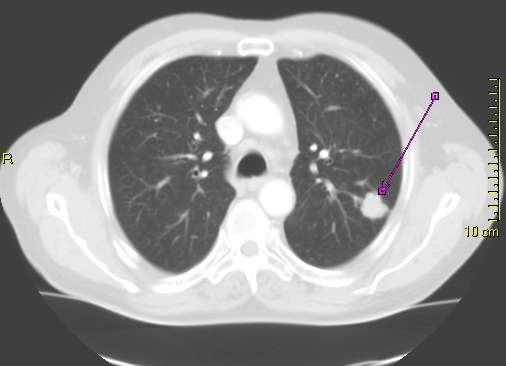

A CT scan that shows a tumour in the posterior part of the left lung

|

|

|

|

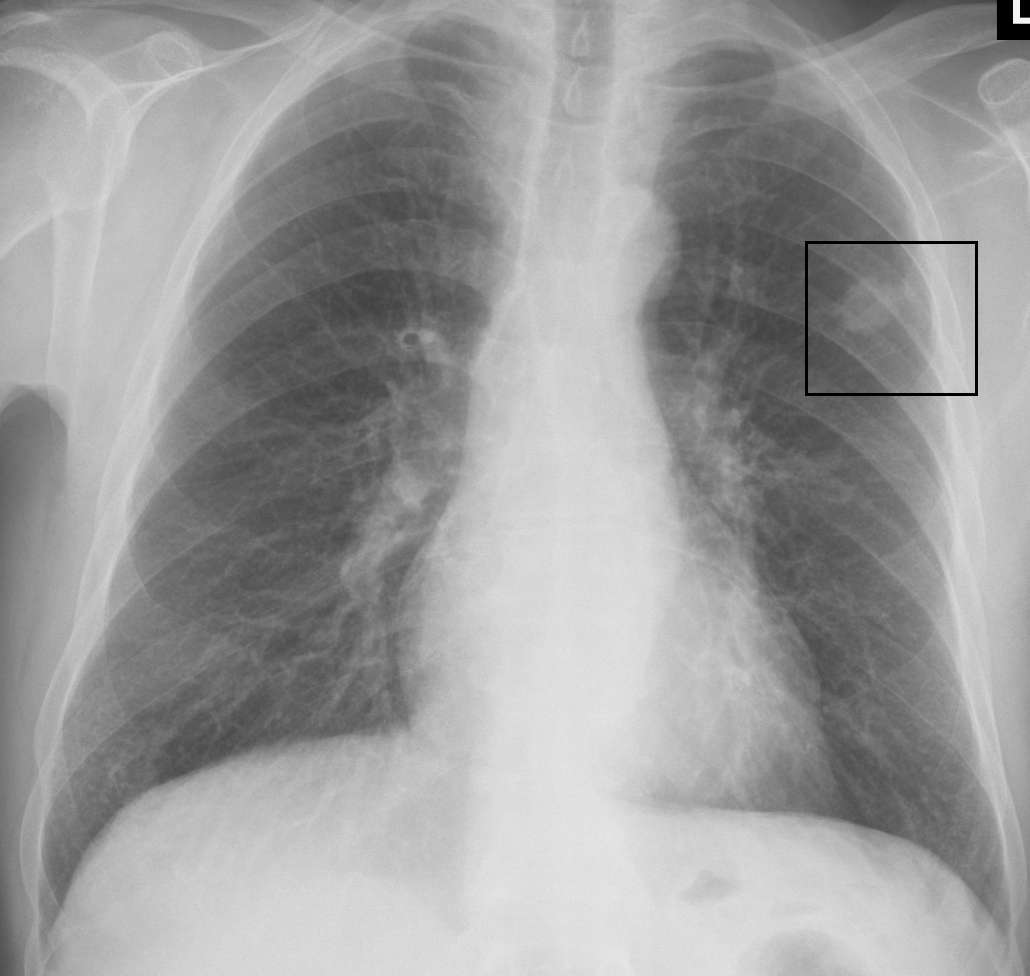

A chest X-ray of a small tumour in the lower part of the left upper zone

|

A chest X-ray of a right sided Pancoast tumour (marked with a P)

X-ray images courtesy of Wikipedia

|

Treatment

The treatment of bronchial carcinoma exhibits a dichotomy between small cell carcinoma and non-small cell carcinoma. Small cell carcinoma requires chemotherapy, possibly supplemented by radiotherapy. Surgery is avoided in small cell carcinoma because the tumour has usually metastasised at the time or presentation. Even though the initial response rates to the chemotherapy are high relapse is frequent and most patients do not live longer than 18 months; without chemotherapy survival to 18 weeks is unusual.

Surgery is considered for non-small cell carcinomas, provided that they are of a sufficiently low stage. However, of those patients who do have early stage disease, a significant proportion have a degree of COPD which means they cannot tolerate the loss of lung volume that the lobectomy or pneumonectomy necessary to remove the tumour would entail. For these two reasons the majority of patients are not suitable for surgery and have palliative radiotherapy. The five year survival for stage one disease is only 50%; stage two drops to 27%, stage three falls to 16% and the median survival for inoperable cases is 5 months.

Other Tumours

Although bronchial carcinoma dominates primary pulmonary neoplasia it is not the only primary tumour of the lung.

Carcinoid tumours can occur. Pulmonary carcinoid tumours secrete into the systemic circulation and may therefore be more likely to be associated with carcinoid syndrome than gastrointestinal carcinoid tumours. The term carcinoid is retained when dealing with lung tumours whereas in other organs it has been superseded by well differentiated neuroendocrine tumour.

Pulmonary hamartomas are small, well circumscribed lesions that are composed of lobules of mature cartilage which feature clefts lined by respiratory epithelium.

Various types of lymphoma can be primary within the lung.

The lung is a common site for metastatic deposits and this should always be borne in mind when dealing with a solitary mass lesion.