Contents

Introduction

Jaundice is a yellow discolouration of the skin, conjunctiva and mucous membranes caused by an accumulation of bilirubin secondary to raised levels of bilirubin in the blood (hyperbilirubinaemia). The term icterus and the related adjective icteric are sometimes used in place of jaundice.

The normal levels of bilirubin in the blood are around 0-20micromol per litre. Jaundice may not be visible until the concentration of bilirubin in the blood is at least twice the upper limit of normal. Jaundice often first becomes noticeable in the sclerae of the eyes, where the bilirubin is actually within the conjuctiva covering the sclera, rather than the sclera itself.

Jaundice can often be associated with itching (pruritus).

|

Picture of jaundice

Image courtesy of Wikipedia

|

Bilirubin

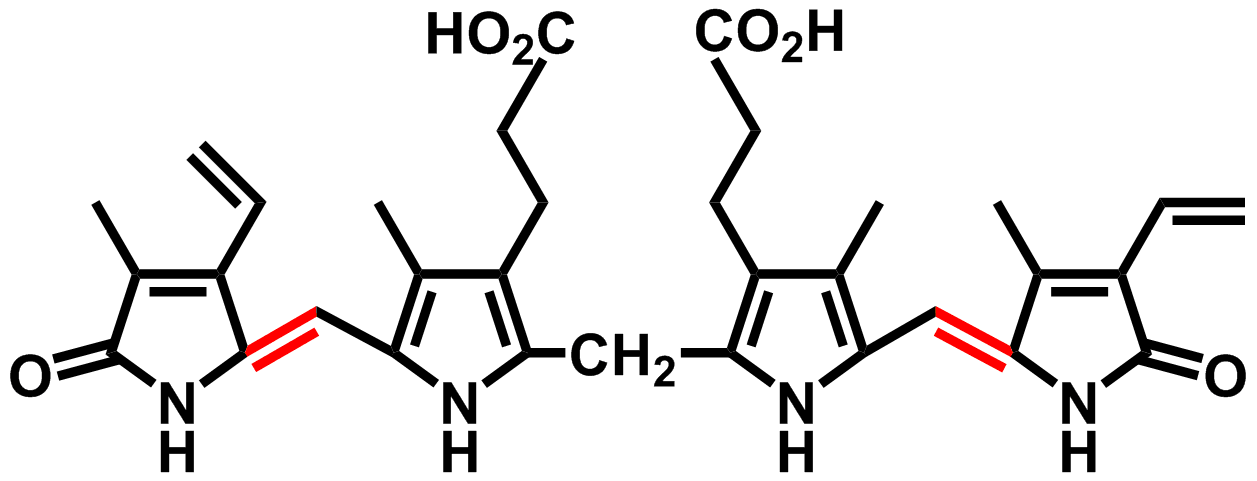

Bilirubin is a breakdown product of the haem component of haemoglobin and is formed when erythrocytes are degraded (principally in the spleen). Haem is converted first to biliverdin, then to bilirubin by biliverdin reductase.

|

Diagram of bilirubin

Image courtesy of Wikipedia

|

Bilirubin is transported to the liver in the blood. The low water solubulity of bilirubin means that it is carried in the blood bound to albumin. In the liver hepatocytes attach glucuronic acid to the bilirubin. This glucuronidation renders the bilirubin more water soluble and amenable to being excreted in the bile.

The bilirubin travels in the lumen of the small bowel to reach the colon. In the colon bacteria convert bilirubin to urobilinogen. Some of this urobilinogen is further converted to stercobilionogen, which is excreted in the faeces and gives them their brown colour. The remaining urobilinogen is actually reabsorbed and is excreted in the urine by the kidneys; urobilinogen imparts the yellow colour to the urine.

Only a very small quantity of unconjugated bilirubin is excreted in the urine.

Causes of Jaundice

The metabolism and excretion of bilirubin can be perturbed in various places and this generates a rather long list of causes of jaundice. These causes are divided into three categories, which as well as helping memorisation and understanding also have some diagnostic usefulness.

Prehepatic

In prehepatic jaundice the rate of production of bilirubin by the breakdown of red cells exceeds the capacity of the liver to deal with the rate of delivery of bilirubin to it. Despite its tremendous general chemical processing capacity the liver can be overwhelmed by surges in bilirubin, even though the function of the liver itself is intact.

The only real source of large quantities of bilirubin is the accelerated destruction of many erythrocytes and thus the causes of prehepatic jaundice are basically the same as the causes of haemolytic anaemia.

Hepatic

Jaundice of hepatic origin occurs when the ability of the liver to deal with normal loads of bilirubin is compromised. It is therefore potentially a feature of any of the diseases that cause acute hepatitis, chronic hepatitis or cirrhosis. However, in addition to these general causes there are some liver diseases that specifically interfere with the handling of bilirubin by the liver.

Gilbert's syndrome is an inherited disease in which there is a mild deficiency of the enzyme glucuronyl transferase. This is the enzyme that is responsible for glucuronidating bilirubin and making it water soluble for excretion in the bile. Under normal circumstances the patient has only a mild hyperbilirubinaemia that is not sufficient to cause jaundice. However, if the patient has an intercurrent illness, such as an infection, or fasts, undergoes surgery or undertakes heavy exertion, then the defective function of the glucuronidation can become swamped and mild jaundice develops.

Crigler-Najjar syndrome also affects glucuronyl transferase. The type I form is rare and autosomal dominant and is produced by an absence of glucuronyl transferase; it presents in neonates with severe jaundice. Type 2 Crigler-Najjar syndrome shows a partial deficiency of glucuronyl transferase that presents with jaundice either in the neonatal period or in later childhood.

Dubin-Johnson syndrome is an autosomally inherited condition in which there is impaired excretion of bilirubin into the biliary system. The disease affects both homozygotes and heterozygotes, the former to a greater extent. The centrilobular region of the liver displays a dark pigment.

Rotor syndrome is an autosomal recessive disease that is caused by impaired storage of bilirubin by the liver.

On a more general level, hepatic jaundice may reflect either impaired glucuronidation of the bilirubin and/or defective excretion of bilirubin into the biliary system. The latter phenomenon is a form of cholestatic jaundice, where cholestasis is a term that denotes an interruption to the flow of bile in the biliary tree. Both types can be caused by drugs.

Posthepatic

Posthepatic jaundice is due to obstruction to the flow of bile in the extrahepatic biliary tree and is frequently referred to a obstructive jaundice. As well as producing jaundice this obstruction also prevents bile from reaching the small bowel and therefore can result in malabsorption of fats.

Various causes of posthepatic jaundice exist.

The close proximity of the common bile duct to the head of the pancreas means that conditions which enlarge the head of the pancreas (such as neoplasia, oedema or fibrosis) can compress the common bile duct.

There is a group of helminths that can take up residence in the biliary tree and in so doing may block it. These parasites do not exist in the United Kingdom can be encountered in the Far East. They may be referred to as liver flukes. Examples are opisthorchis viverreni and clonorchis sinensis.

A choledochal cyst is a developmental abnormality of the biliary tree in which part of the biliary tree is dilated.

Biliary atresia affects around 1 per 10000 live births and is a disease in which there is fibrotic occlusion of all or part of the extrahepatic biliary tree.

Obstructive jaundice is particularly likely to be associated with pruritus.

Conjungated or Unconjugated

Jaundice can also be classified on the basis of whether or not the elevated bilirubin is of the conjugated type, the unconjugated type or both.

Conjugated hyperbilirubinaemia indicates that the liver has processed the bilirubin and that the problem lies with excretion after the act of conjugation. Thus, it tends to equate to obstructive jaundice.

Unconjugated hyperbilirubinaemia denotes a failure of the liver to conjugate the bilirubin and is seen in either prehepatic or hepatic jaundice.

A mixed unconjugated and conjugated pictures implies either dual pathology or hepatic jaundice.

Kernicterus

Kernicterus is a complication of jaundice that is peculiar to neonates. The neonatal brain is vulnerable to damage by hyperbilirubinaemnia because the blood-brain barrier is not fully formed. Bilirubin can therefore enter the brain and irreversibly damage neurones. In some cases this damage can be severe or even fatal. The problem is exacerbated by the fact that the hepatic mechanisms for processing bilirubin are not fully developed in neonates.

Phototherapy can breakdown bilirubin in the skin and thus reduce its levels in the blood.

The concentration of bilirubin required to produce kernicterus is significantly greater than that which occurs in the common mild jaundice that is seen in neonates.

Investigations

The diverse causes of jaundice can require extensive investigation, but the focus can be narrowed by determining the basic type of jaundice. This can be achieved by examining the urine, stools and determining whether the bilirubin in the blood is of the conjugated or unconjugated form.

In prehepatic jaundice the hyperbilirubinaemia is produced by unconjugated bilirubin (in effect this bilirubin is in a queue waiting to be processed by the liver). The unconjugated bilirubin is not water soluble so levels of bilirubin in the urine are not elevated. The stools are normal because the rate of delivery of bilirubin to the bowel is not compromised.

The hyperbilirubinaemia of posthepatic jaundice is formed by conjugated bilirubin. This conjugated bilirubin spills over into the urine and makes the urine much darker than usual. By contrast the faeces are pale because they are deprived of stercobilinogen.

The situation in hepatic jaundice can be more complicated because the problem can be either impaired conjugation, defective excretion, or both. The presence of urobilinogen in the urine is an indication that at least some bilirubin is entering the bowel because the colon is the source of the urobilinogen.

Liver function tests are vital in the investigation of jaundice and not simply because they include a measurement of bilirubin. Jaundice due to a problem with the excretion of bile will tend to be associated with liver function test in which the most marked change is an elevation of the alkaline phosphatase. If the jaundice is produced by damage to hepatocytes, a raised alanine transaminase will tend to dominate.

Serology for hepatitis viruses is often performed in the investigation of jaundice.

Ultrasound of the liver and biliary system is useful in excluding or confirming an obstructive cause.

The full blood count and other haematological investigations can pursue a haemolytic anaemia.