Introduction

The evaluation of the relationship of a tumour to the resection margins of a specimen is a key element in the dissection of an excision specimen of a tumour.

The presence of the tumour at a resection margin is often an indication that further treatment may be necessary and can be associated with an increased risk of recurrence and a worse prognosis.

In many tumours not only is it necessary to determine if the tumour is present at the margin but to establish the distance of the tumour from the margin. In such cases if a tumour is within a certain distance of the margin, even if not demonstrably at the margin, the proximity is deemed sufficient to regard the margin as being involved. For example, a clearance of at least 1mm from the circumferential margin is required in the case of a rectal adenocarcinoma.

The distinction must be made between a

surface and a

margin. For the purposes of specimen dissection, a margin is a boundary of a specimen which was made by the surgeon cutting through something. A surface is merely a pre-existing outer part of the specimen and did not require any surgical incisions. For example, the epidermis of an ellipse of skin is a surface but the edge of the subcutaneous tissue is a margin.

This distinction is important because the presence of disease at a margin implies that part of the lesion remains in the patient. Involvement of a surface may alter the staging of a tumour but is not something over which the surgeon has control. Surgeons may become perturbed if disease involvement of a surface is wrongly ascribed as incomplete excision on their part. More importantly, confusing surfaces and margins may lead to inaccurate staging and suboptimal treatment.

Cruciate or En Face

The decision as to whether a margin should be sampled with cruciate (longitudinal) blocks or en face blocks can provoke considerable debate. Any contentious issues in the choice are centred on the fact that en face and cruciate blocks evaluate margins in mutually exclusive ways.

En Face

An en face block, sometimes known as a shave, allows the entire margin to be examined.

Unless the tumour has a completely discontiunous pattern of growth (in other words shows skip lesions or satellites lesions), a negative en face block means that tumour cannot have reached the margin because it would have to pass through the en face section in order to extend to the margin.

However, this information is largely binary in nature and gives a yes / no statement (involved / not involved). The distance from the tumour to the margin cannot be measured microscopically. A macroscopic measurement of the margin gives some information but cannot be confirmed microscopically.

As some tumours can infiltrate beneath normal overlying mucosa without producing any changes that are visible macroscopically, the en face block alone may not be enough to confirm the absence of this process in the tissue that spans the gap between the en face block and the macroscopic limit of the tumour. Measuring the thickness of the en face block when it is produced can be helpful, but facing up the block when sections are cut will remove a variable and unpredictable amount of this thickness.

|

|

|

|

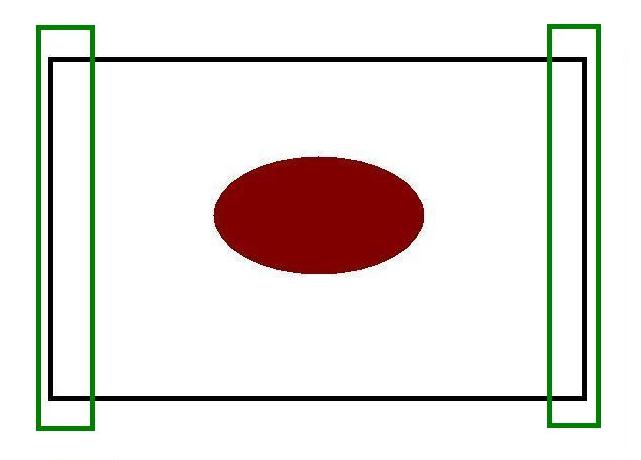

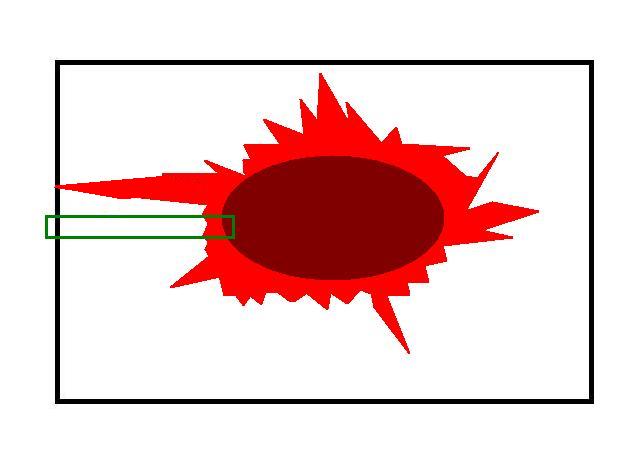

The green blocks indicate en face margins for the maroon tumour.

|

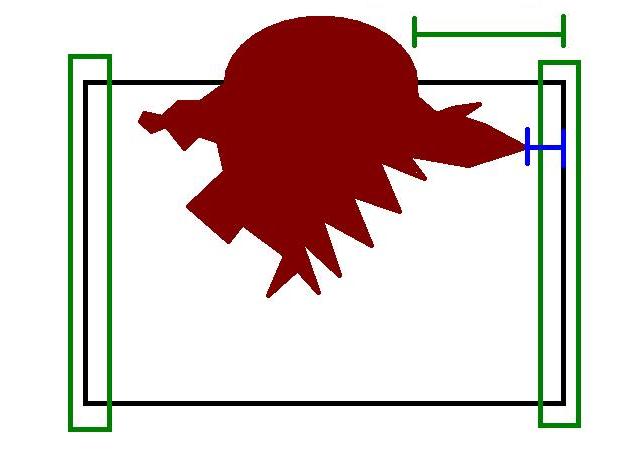

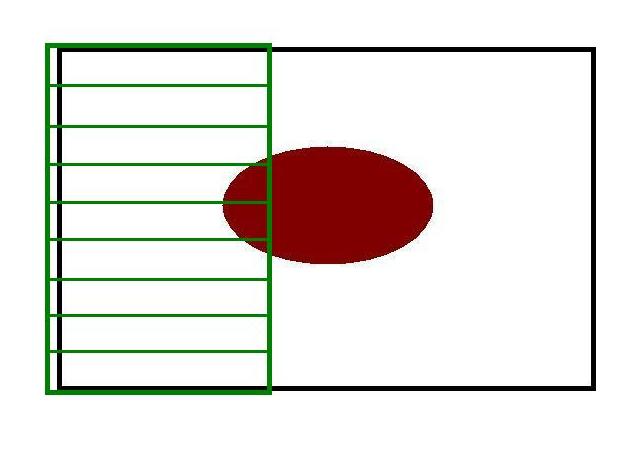

The green bar shows the macroscopically measured margin while the blue bar denotes the true margin produced by deep tumour that is not visible from the surface.

|

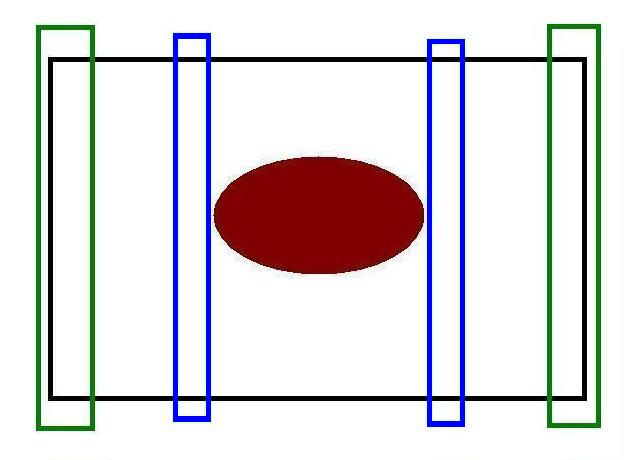

The use of flanking blocks (blue) can tackle the problem of concealed tumour. The flanking blocks are taken on the edge of the macroscopically visible tumour and reveal if the macroscopic impression of the extent of the tumour is accurate or not.

|

Cruciate

The cruciate block solves the considerable limitations of measurement posed by en face blocks (although the converse is also true). However, cruciate blocks are only valid if the tumour can be reliably identified macroscopically. The problem of tumour invading beneath normal mucosa again causes difficulties. The cruciate block addresses this issue for the part of the margin it samples, but a cruciate section samples only a minority of the margin. A tumour that possesses a very irregular border may be particularly likely to give a false negative evaluation of the margin status if a cruciate block is used.

The drawbacks to cruciate sections can be partially ameliorated if the entire margin is embedded as cruciate sections. This approach will generate considerably more blocks than the en face method, sometimes to the point of being prohibitive. In addition, the same sampling error that affects a single cruciate block still applies to multiple cruciate blocks, albeit with a lesser degree of a false negative assessment of the margin occurring. While the entire margin may be embedded by multiple cruciate blocks, the blocks will be around 3-5mm thick yet only one or two 5 micrometre thick sections will be cut from each block. The potential for tumour to be reaching the margin in the uncut (or trimmed) tissue persists.

|

|

|

|

The green blocks indicate the cruciate margins for the maroon tumour.

|

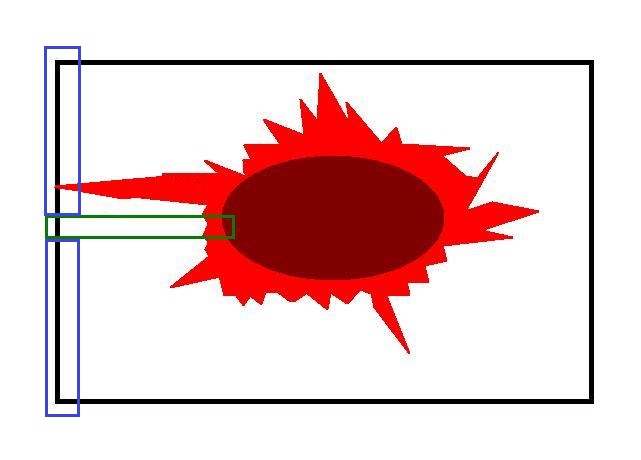

The maroon component of the tumour indicates the portion of the tumour that can be discerned macroscopically. The red element represents the true boundaries of the tumour. If a cruciate block (green) is used, the long, infiltrating tongue of tumour that reaches the margin could be missed.

|

Parallel cruciate sections reduce the chances of a narrow band of tumour escaping detection by cruciate blocks.

|

Comparison

Ultimately, the technique that is employed will depend upon the tumour and its treatment.

If a simple yes / no statement as to the margin is adequate, supplemented by the inference that a negative en face block implies a distance to the margin of at least 1-5mm, an en face method may be adopted.

En face blocks are popular in colorectal excisions that have a good macroscopic clearance (typically at least 10mm) and in general in situations where the macroscopic distance from the tumour to the margin exceeds the length of a normal block. En face embedding of the poles of a skin ellipse is also common.

However, if microscopic determination of the distance to the margin is critical, often when the nature of the excision is such that even with optimal surgery the clearance between the tumour and the margin will be relatively narrow, cruciate blocks are needed so that a precise measurement can be obtained. Examples of situations where this may pertain are maxillofacial resections where the local anatomy means that generous margins are not surgically feasible, or low rectal tumours, where preservation of the anal sphincters again requires a narrow margin.

Sometimes, a combination of the two techniques is the optimal method. The closest macroscopic approach of the tumour to the margin can be embedded with one or two cruciate blocks and the rest of the margin embedded en face.

|

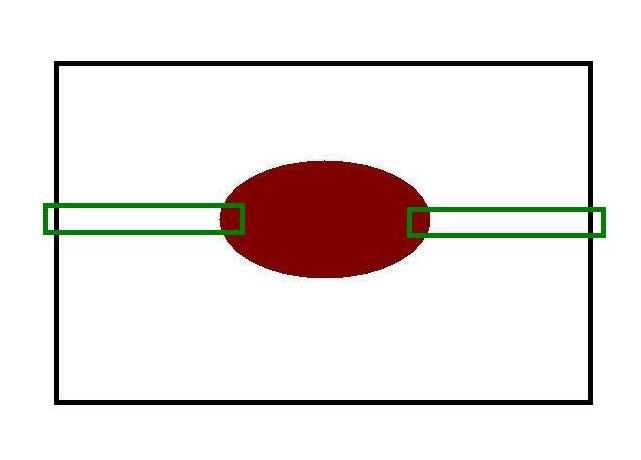

In this case, a cruciate block (green) has been taken for measurement purposes. The two blue en face blocks allow the rest of the margin to be examined and should detect the concealed tongue of tumour

|