Contents

Introduction

Peptic ulcers are ulcers of the gastrointestinal tract that are occur when the mucosa is damaged by gastric acid. The usual sites are the stomach and the duodenum. The oesophagus can occasionally be involved if

gastro-oesopahgeal reflux disease is present. Rare sites of involvment include a Meckel's diverticulum or if upper GI surgery has previously been performed in anastamoses between the stomach and oesopahgus or jejunum.

Peptic ulcers tend to occur in middle age and later life and are slightly more common in males.

Pathology

The mildest form of peptic ulcer disease is the small, superficial erosion. Such a lesion can be multiple and occur during acute severe stress, such as burns or septicaemia. The increase in gastrin levels that is caused by corticosteroids may be relevant.

Acute ulcers tend to be related to non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs or alcohol. They are deeper than erosions.

Chronic ulcers are encountered in association with helicobacter pylori infection and/or NSAID use.

Peptic ulcers are usually well defined and may be described as having a punched-out appearance due to the steep contour of the walls. The edges overhang the ulcer. In the stomach the rugae converge on the edges of the ulcer. The ulcers are usually 1 to 3cm in size but can reach 10cm.

Gastric ulcers are typically single and are frequently located on the lesser curve of the stomach at the junction between the antrum and the body. Duodenal ulcers are often present as a pair, one on the anterior aspect of the mucosa and one on the posterior aspect of the mucosa (kissing ulcers); the first part of the duodenum is the typical site of involvement. Gastric and duodenal ulcers can co-exist.

The defining pathology of an ulcer is a discontinuity in a mucosal surface. The base of an ulcer often displays granulation tissue and peptic ulcers are no exception. The wall of the stomach beneath the granulation tissue shows fibrous scarring in chronic ulcers, although acute ulcers may heal without scarring. The mucosa at the edges of the ulcer and that which re-covers the ulcer during healing can manifest reactive nuclear change.

Peptic ulcers may extend deeply into the wall of the stomach or duodenum and can sometimes erode into a large blood vessel and produce significant haemorrhage, which in some instances may be fatal. Even deeper penetration of the ulcer leads to perforation of the stomach or duodenum and the development of peritonitis.

In addition to the acute complications of haemorrhage and perforation, peptic ulcers can induce chronic distortion of the stomach or duodenum due to the fibrotic healing response. If this distortion is clinically apparent it is usually in the form of obstruction of the organ.

Helicobacter Pylori

Helicobacter pylori is a Gram negative, flagellated spiral coccobacillus that has made its niche in living in the acidic environment of the stomach. It is implicated in around 95% of duodenal ulcers and approximately 70-80% of gastric ulcers, although these figures are falling.

The ability of helicobacter pylori to produce the enzyme urease is integral to the organism's tenacity in surviving in a sea of hydrochloric acid. Urease breaks down urea into ammonia and carbon dioxide. This reaction allows the bacteria to generate energy and also yields ammonia which can neutralise the acid in the vicinity of the helicobacter pylori.

In order to ensure a supply of urea and other goodies, some strains of helicobacter pylori are equipped with extra pieces of kit that allow them to make the most of their new home. The vacuolating toxin subtype 1 creates holes in gastric epithelial cells to cause them to lose their intracellular contents; apoptosis is also induced and the function of nearby T cells can be impaired. The cagA protein stimulates the proliferation of the gastric epithelial cells.

|

|

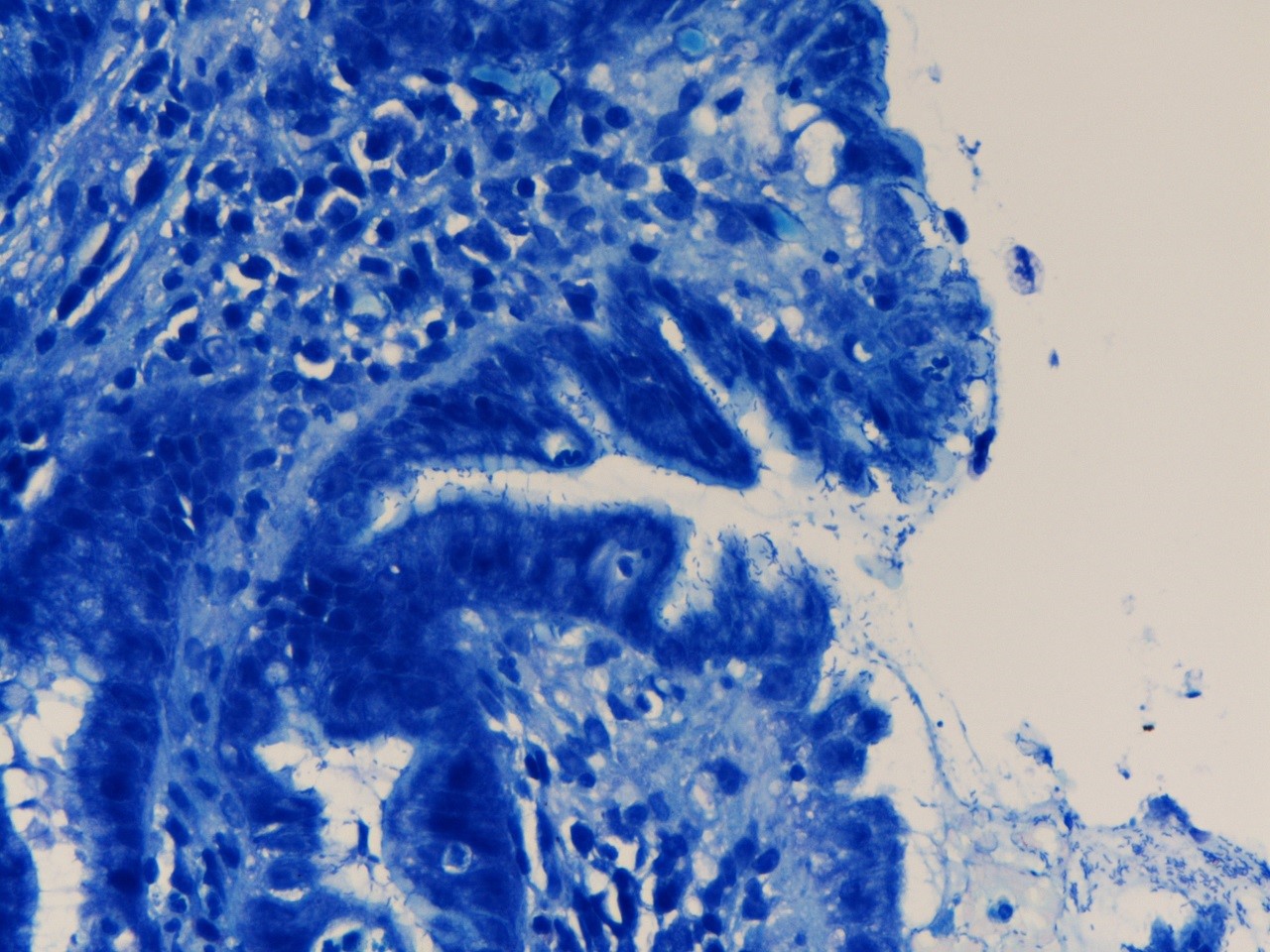

Giemsa stain of a gastric biopsy that shows helicobacter pylori.

|

The presence of helicobacter pylori and especially its urease enzyme induces a chronic inflammatory response. This can disrupt the usual mechanisms of bicarbonate and mucin secretion which protect the stomach mucosa against acid and thus a gastric ulcer can result (around 5-10% of cases of helicobacter pylori infection). Alternatively, the chronic inflammation induced by the helicobacter pylori can damage the D cells of the antrum, which normally release somatostatin that suppresses the secretion of gastric acid. Hence, the levels of gastric acid rise and this does not go down well with the duodenal mucosa, which ulcerates (5-15% of infections). In order to cope with the acid, the duodenal mucosa may undergo gastric metaplasia.

Other patients who have helicobacter pylori infection develop severe inflammation that causes atrophy of the gastric mucosa. The atrophic gastric mucosa cannot make acid. Being somewhat confused by this achlorhydria, the stomach undergoes intestinal metaplasia and this can be the first step on the road to a series of mutations which culminate in

gastric adenocarcinoma (1-3% of infections).

Less than 1% of cases of helicobacter pylori infection are complicated by the development of an extranodal marginal zone lymphoma of the stomach. The persistent infection in these patients induces the formation of mucosa associated lymphoid tissue in the stomach. Failure to clear the infection causes repeated rounds of mutation in the B cells as they attempt to respond to the infection and ultimately a clonal B cell population that is driven by the helicobacter pylori infection may emerge.

The majority (80%) of patients who have helicobacter pylori infection have a mild degree of inflammation and are asymptomatic. A mild reduction in acid secretion occurs and this may actually lower the incidence of Barrett's oesophagus and adenocarcinoma of the oesophagus.

|

|

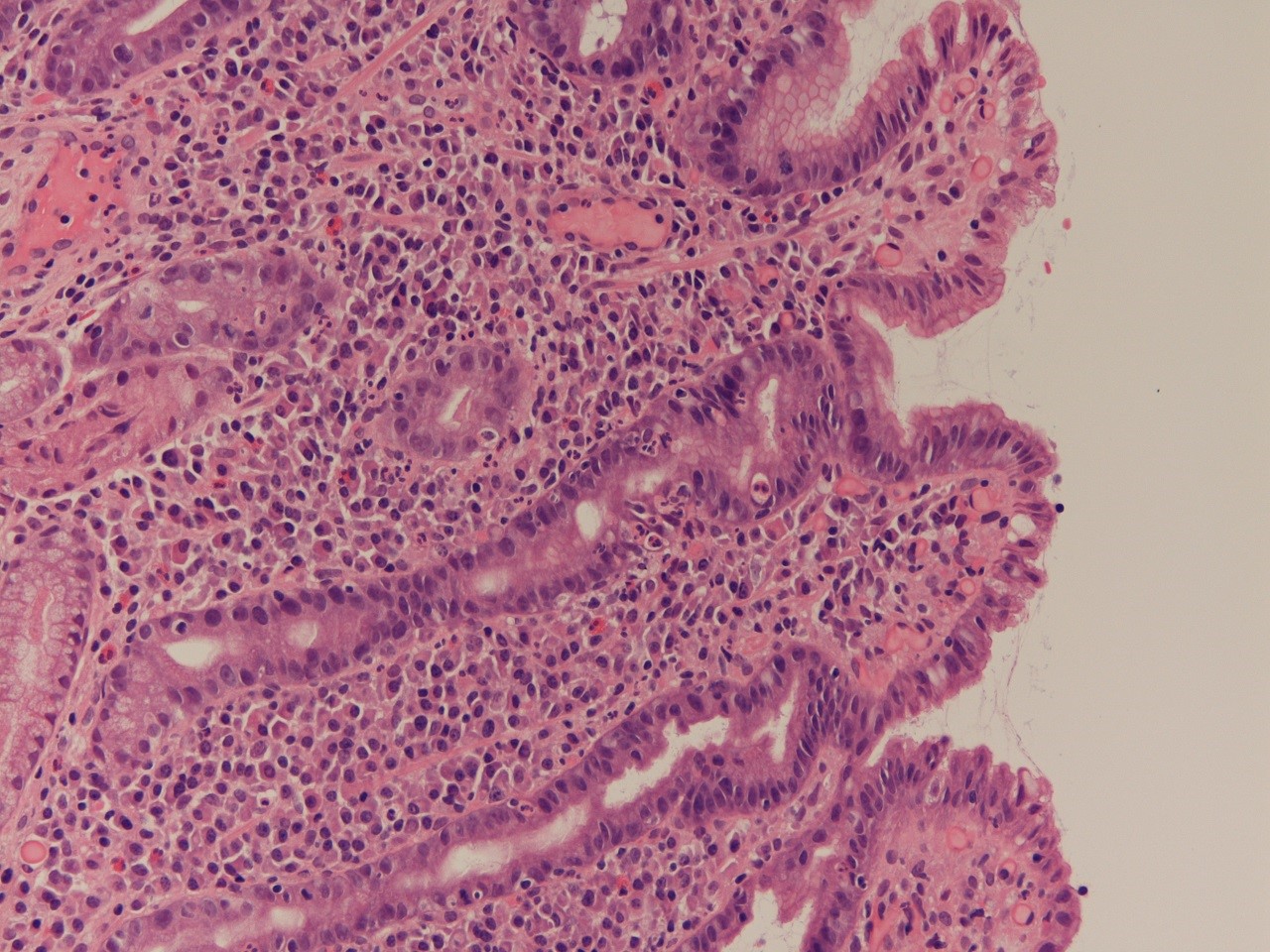

This gastric biopsy exhibits acute and chronic inflammation secondary to helicobacter pylori.

|

NSAIDs

Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs such as aspirin, ibuprofen and diclofenac (voltarol) are implicated in an increasing number of peptic ulcers. NSAIDs inhibit cyclo-oxygenase, which is the enzyme that initiates the conversion of

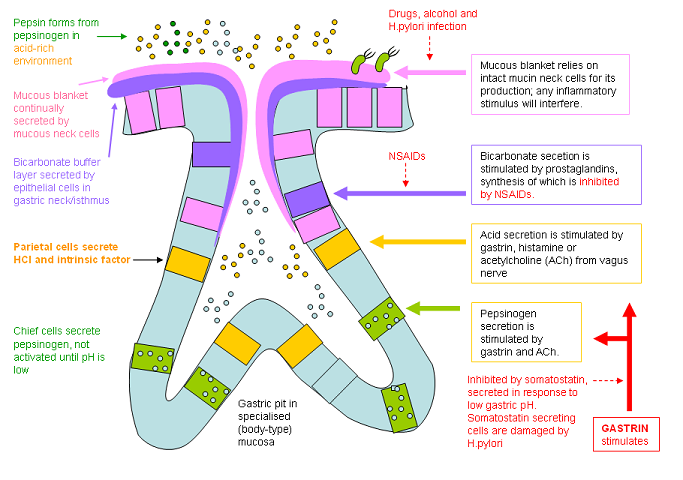

arachidnoic acid into prostaglandins. Prostaglandins stimulate the secretion of bicarbonate by the gastric mucosa. This bicarbonate is trapped beneath the layer of mucin that covers the gastric mucosa and thus helps to defend the stomach against attack by the gastric acid. NSAIDs inhibit this defensive mechanism and thus render the mucosa susceptible to ulceration.

|

Diagram to show the mechanisms that influence the secretion of gastric acid and the defences against gastric acid.

Diagram courtesy of Dr C Finlayson

|

Zollinger-Ellison Syndrome

Zollinger-Ellison syndrome is a rare disease that has an incidence of around 1 per 1000,000 per year and is caused by a low grade neuroendocrine tumour of the pancreas that secretes gastrin. The autonomous, unregulated release of gastrin causes excessive production of gastric acid. This can lead to peptic ulceration. The ulcers can be multiple and extend more distally into the duodenum than is usual in other forms of peptic ulceration.

Clinical Features

Peptic ulcers tend to present with epigastric pain that may be precipitated or exacerbated by food (gastric ulcers) or relieved by food (duodenal ulcers, although the distinction is not as absolute as some might assert) and can be relieved by antacids. The pain is commonly associated with vomiting (more so with gastric ulcers). The symptoms may persist for several weeks, then resolve for a period of time.

Bleeding from the ulcer can result in iron deficiency anaemia, haematemesis or malaena. The haemorrhage can be dramatic and life-threatening.

Perforation causes severe abdominal pain and peritonitis.

Investigations

Upper GI endoscopy is the preferred way to confirm a diagnosis of a peptic ulcer because it allows a biopsy to be taken, unlike a barium meal. It is important to repeat the endoscopy six weeks later in order to check that the ulcer has healed. It if has not it could be because the ulcer is actually malignant.

A full blood count is prudent to determine if anaemia has resulted from chronic blood loss.

Treatment

If the patient is taking NSAIDs these should be stopped if possible.

Helicobacter pylori can be eradicated with antibiotic therapy in combination with a proton pump inhibitor.

Endoscopic treatment of an actively bleeding ulcer may be possible.

Perforation requires either repair of the ulcer by oversewing or resection.

Before the role of helicobacter pylori in peptic ulcer disease was fully elucidated surgery was a common form of treatment and could involve either cutting the branches of the vagus nerve that supplied the stomach (vagotomy) or removing the gastric antrum. This treatment is now fading into the history books.