Contents

Anatomy

The uterus is a hollow, muscular organ that is the normal site of implantation of the blastocyst and the subsequent development of the blastocyst into a mature fetus.

The uterus has at least two dead language prefixes associated with it: both hyster and metra refer to the uterus.

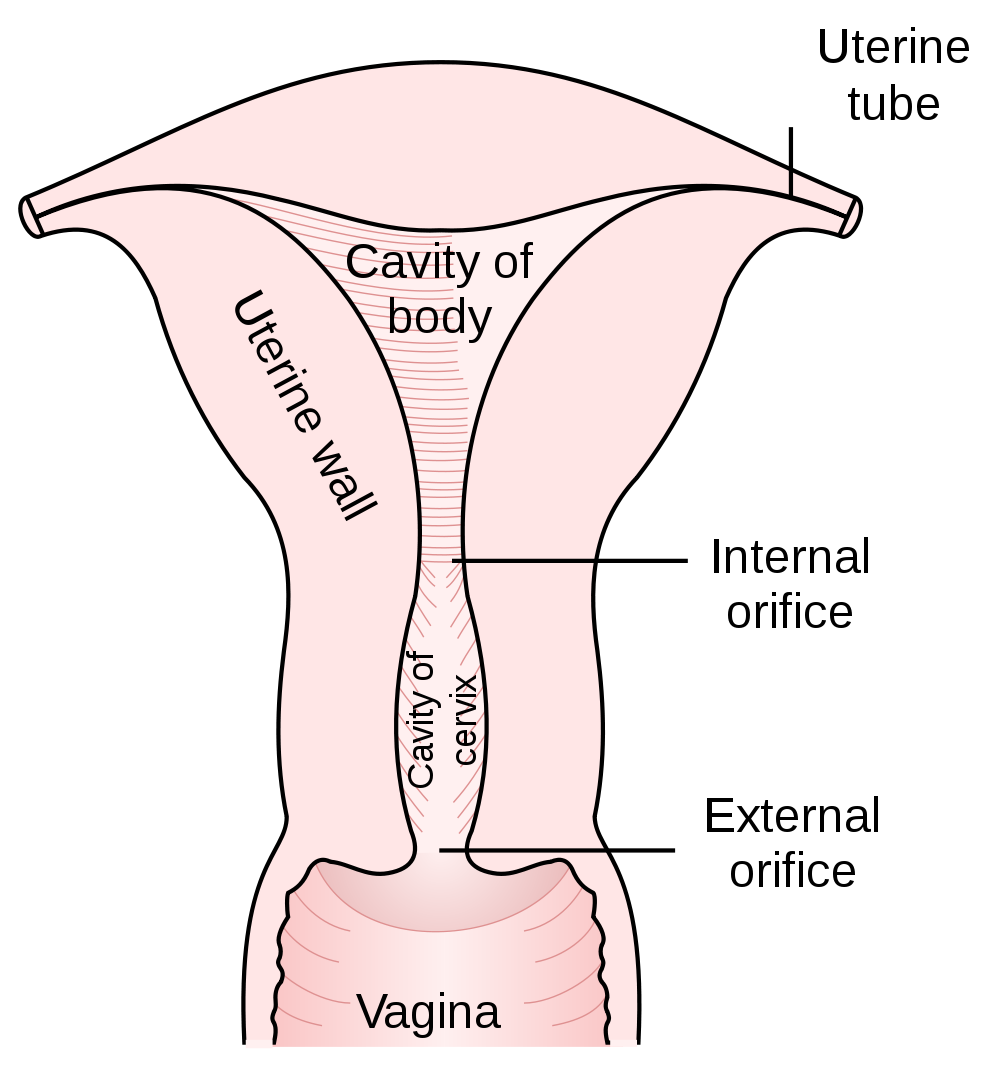

The uterus is divided into several portions.

The fundus is the portion of the uterus that is located superiorly to the plane formed by level of entry of the fallopian tubes.

The body of the uterus forms the bulk of the organ and extends from the fundus above to the isthmus below. It houses the vast majority of the cavity of the uterus, which is where the fetus develops.

The isthmus is located below the body of the uterus and is a constriction of approximately 10mm in length. The terms internal os or internal orifice may sometimes be employed instead of isthmus

Despite often being considered to be an organ in its own right, the cervix is actually part of the uterus; its formal name is cervix uteri. It has a centrally located endocervical canal which communicates with the cavity of the body of the uterus above via the internal os and with the vagina below via the external os. The cervix projects into the vagina; this is the vaginal part of the cervix; the portion of the cervix that lies above the top of the vagina is the supravaginal part. The external portion of the cervix has diameters of around 25-30mm and is divided into anterior and posterior lips.

|

Diagram of the parts of the uterus

Diagram courtesy of Wikipedia

|

The normal arrangement of the uterus relative to the vagina is for the fundus of the uterus to be pointing upwards while the vagina is directed backwards and upwards. This is known as anteversion. The angle is usually around 90 degrees. The body of the uterus is often bent forwards relative to the isthmus: anteflexion. If the opposite arrangements apply the terms retroversion and retroflexion are employed as necessary.

Structure and Histology

The wall of the uterus has the three layered basic structure of which the body is so fond. The outer layer is the serosa and is formed in part by peritoneum; it is sometimes called the perimetrium. The middle layer constitutes the bulk of the uterus and is composed of smooth muscle. It is known as the myometrium. The innermost layer of the uterus is its mucosa, which is dubbed the endometrium. The endometrium is a form of glandular mucosa. The portion of the endometrium situated immediately adjacent to the myometrium is the basal layer while that above the basal layer is the functional layer. The structure of the endometrium changes during the phases of the

menstrual cycle.

The endocervical canal is lined by mucinous glandular mucosa. The outer portion of the cervix, the ectocervix, is covered by non-keratinising stratified squamous mucosa. The junction between the the two types of mucosa is called the transformation zone. The precise position of the transformation zone is not constant: it can move during the

menstrual cycle and this induces metaplasia in the glandular mucosa to squamous mucosa when the glandular mucosa becomes exposed. A shift in the position of the transformation zone also occurs during puberty and is known as eversion.

Blood, Lymphatic and Nerve Supply

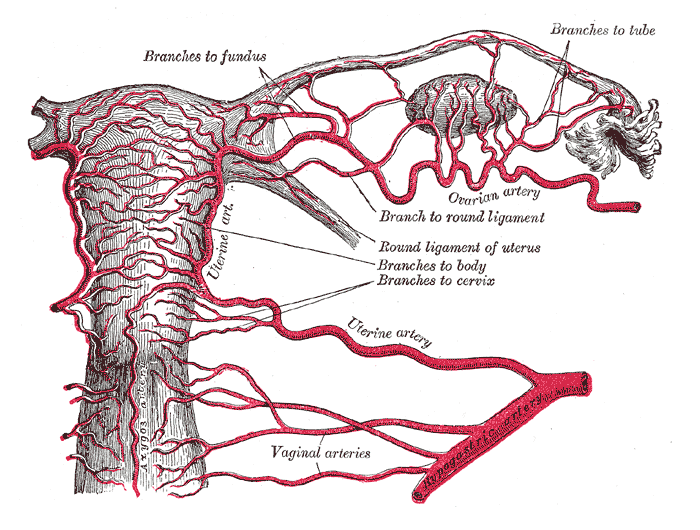

The arterial blood supply of the uterus is from the appropriately named right and left uterine arteries. Each half of the uterus has one uterine artery, which is a branch of the internal iliac artery. The uterine artery reaches the cervix first, then runs upwards along the side of the uterus before turning to run along the bottom of the fallopain tube.

The veins correspond to the arteries.

The lymphatic drainage of the upper part of the uterus is to the lumbar and para-aortic lymph nodes. The drainage from the lower part of the body of the uterus is to the external iliac lymph nodes. The drainage of the cervix is to the external iliac lymph nodes, internal iliac lymph nodes and the sacral lymph nodes.

The innervation of the uterus is by the autonomic nervous system.

|

Diagram of the blood supply of the uterus

The hypogaastric artery is another name for the internal iliac artery

Diagram courtesy of Wikipedia

|

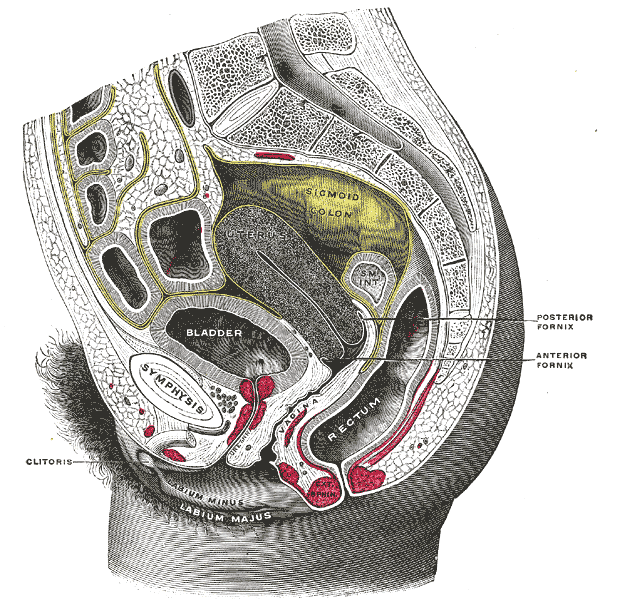

Relations

The bladder is located in front of the uterus; the sigmoid colon and upper rectum are situated posteriorly. The fallopian tubes are in continuity with the uterus in its upper lateral portion and the ovaries are located lateral to the uterus. The vagina is below the uterus. The peritoneal cavity and the small bowel within it are above the uterus.

|

Sagittal section of the female pelvis

Diagram courtesy of Wikipedia

|

Attachments

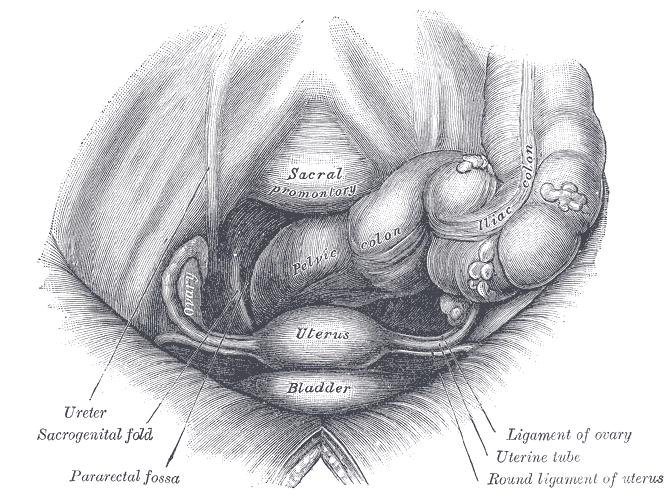

The uterus possesses several attachments to the pelvis.

The location of the uterus below the peritoneal cavity means that the inferior aspect of the peritoneum is draped over the top of the uterus. The presence of the bladder anteriorly and the sigmoid colon and rectum posteriorly means that the peritoneum forms folds in front of and behind the uterus. These are the vesicouterine pouch and the rectovaginal pouch (pouch of Douglas) respectively.

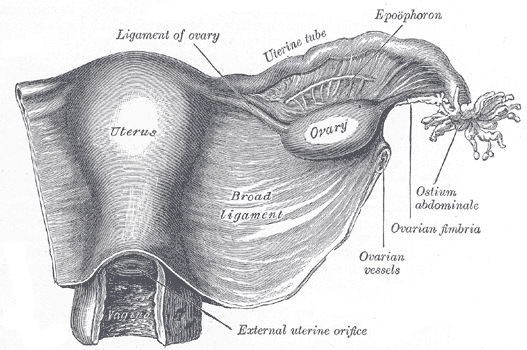

On the lateral sides of the uterus these folds of peritoneum, which are also draped over the fallopian tubes, extend to the pelvic side wall and form the broad ligament. The uterine vessels are contained in the broad ligament.

The round ligament of the uterus is a narrow band of fibrous tissue that runs forwards and laterally from the side of the uterus a little anteroposteriorly to the insertion of the fallopian tube. It curves around the inferior epigastric artery and enters the inguinal canal and runs through the inguinal canal to terminate in the labium majus.

The cardinal ligaments of the uterus are thickenings of the pelvic fasica that extend from the lateral aspect of the cervix into the fascia that covers the levator ani. The uterosacral ligament is a thickening that attaches the posterior aspect of the cervix to the sacrum.

|

|

The female pelvis viewed from above

Diagrams courtesy of Wikipedia

|

The uterus and friends viewed from behind

|

Physiology

The physiology of the uterus is that of the

menstrual cycle and pregnancy.

During pregnancy the smooth muscle of the uterus undergoes hypertrophy. Despite the considerable increase in the size of the uterus during pregnancy its mass tends not to exceed 1kg.

The cervix forms a thick mucus plug during pregnancy that isolates the uterine cavity from the lumen of the vagina.

During labour the uterine smooth muscle contracts. These contractions are very powerful and compress the arteries that penetrate the myometrium. This renders the uterus ischaemic and causes the pain of contractions. In the first stage of labour these contraction serve to dilate the cervix and in the second they expel the fetus. It has been suggested that around 90% of the force that pushes the baby out of the uterus comes from the contractions of the myometrium while only 10% is contributed by voluntary contractions of the abdominal wall and diaphragm.

After delivery is complete the uterus needs to begin the process of returning to its original size. This requires six to eight weeks and is termed involution.

Cut Up

The basic excision specimen of a uterus is the total hysterectomy. This may be coupled with a bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy when it will often be referred to by the abbreviation of TAH BSO (the 'A' denotes abdominal). For benign processes and non-ovarian neoplasms the fallopian tubes and ovaries are removed attached to the uterus. The resection of ovarian tumours may require that the involved tube and ovary are sent separately and thus the uterus may have only one fallopian tube and ovary attached (and sometimes neither if there is bilateral ovarian disease).

The following description of the approach to the cut up of a uterus describes a total hysterectomy with attached fallopian tubes and ovaries. If a les comprehensive specimen is received the relevant aspects can be omitted as necessary.

It should be possible to determine which is the front of the specimen: the peritoneal reflection is higher up and looser on the front of the uterus than on the back; the posterior peritoneal reflection typically tapers over the cervix and is stubbornly adherent. If the ovaries are included they provide an additional landmark because they are positioned on the posterior aspect of the broad ligament and therefore lie slightly behind the fallopian tubes. Determining anterior and posterior allows right and left to be recognised because the shape of the uterus defines superior and inferior.

The description should state the components of the specimen. The vertical, transverse (at the cornua) and anteroposterior dimensions of the uterus should be given. The specimen should also be weighed. The anteroposterior and transverse diameters of the ectocervix are measured and the length of the cervix can be stated; a comment on the appearance of the cervix at this juncture is prudent.

The length and diameter of each fallopian tube should be recorded. Each ovary is measured in three perpendicular planes. The ovary is usually bisected in the coronal plane. This is usually sufficient for normal ovaries, although some may benefit from further bisection of each half. The appearance of the ovary can be noted as this juncture.

The uterus is then opened. Opinion is divided as to which of the two main techniques is the better way to open a uterus. Each probably has its own merits in particular situations.

The standard approach is to bisect the uterus into a left and right side. This is achieved by inserting a probe through the external os of the cervix and then cutting down alongside the probe. This cut will be roughly in the sagittal plane.

Once the uterus is bisected the thickness of the endometrium is measured. The appearance of the endometrium can be noted, although this will typically be along the lines of 'unremarkable'.

The myometrium is exposed by the bisection. If fibroids are present their cut surface will usually have been revealed, although parasagittal slices may be necessary for all but the smallest uterus in order to evaluate the myometrium (and any fibroids) properly.

The alternative method for opening the uterus is to divide it into a front and back half. This technique is usually performed by opening the specimen with scissors. The scissors need to be sharp but tend not to remain that way after many uteruses. The method also often does not go down well with the muscles of the first web space of the hand of the dissector. However, the front and back approach demonstrates the shape of the endometrial cavity better than the left-right method and is better when dealing with a hysterectomy performed for endometrial hyperplasia and some cases of endometrial carcinoma. Opening a fibroid uterus in this fashion can be a challenging experience.

The basic blocks of the uterus that should be taken even if no abnormality is identified are as follows.

- Two blocks of the cervix to show the anterior and posterior aspects and the endocervical canal

- Two full thickness slices of the wall of the uterus at the level of the upper body (endometrium must be included)

- One transverse section of each fallopian tube

- One hemisection of each ovary

These blocks may need to be modified depending upon where the lesion is located and what its nature is. For example, the entire cervix is embedded in cases of cervical carcinoma; the whole fallopian tube may be embedded when dealing with an ovarian tumour.

An example description is given below.

The specimen comprises a uterus with attached fallopian tubes and ovaries. The cervix is present.

The uterus measures 120mm in vertical dimension, 70mm transversly and 50mm anteroposteriorly. The weight is 80g.

The cervix measures 28mm anteroposteriorly, 25mm transversely and has a length of approximately 15mm. The cervix appears unremarkable.

The right fallopian tube has a length of 35mm and a diameter of 10mm. The right ovary measures 30x22x12mm. The left fallopian tube measures 30mm long by 11mm in diameter. The left ovary measures 31x22x14mm. Both ovaries and fallopian tubes appear unremarkable.

Opening the specimen reveals that endometrium has a thickness of 3mm and appears unremarkable. No focal abnormality is identified.

A1+A2) Cervix

A3+A4) Body of the uterus

A5) Right fallopian tube and ovary

A6) Left fallopian tube and ovary