Contents

Lymph Nodes

Lymph nodes are specialised structures in the immune system that may be considered to serve as barracks and observations posts for lymphocytes and their supporting cells.

Lymph nodes are located along the course of lymphatic channels and therefore expose their resident immune cells to the contents of those lymphatics

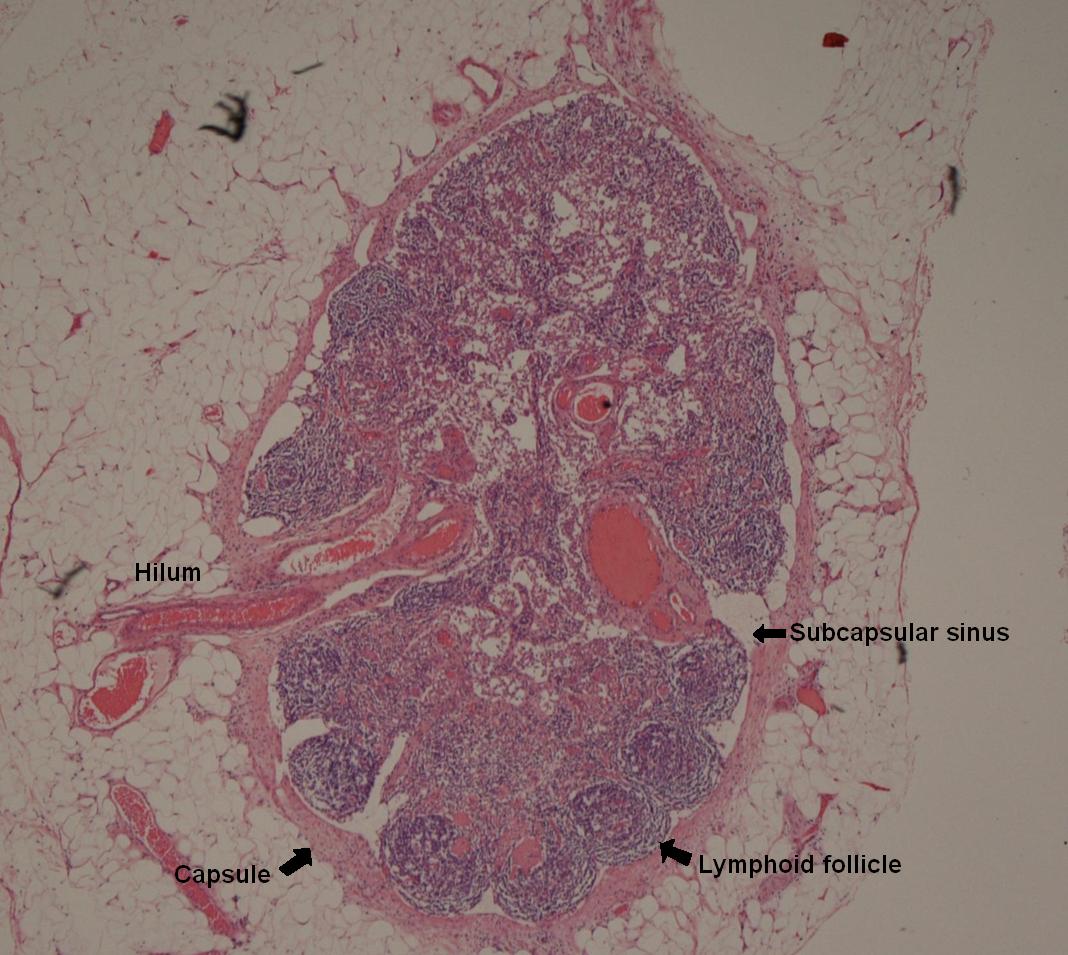

Lymph nodes are ovoid structures and receive lymph via afferent lymphatic channels. The afferent lymphatics enter the node on its periphery and drain into the subcapsular sinus which branches to distribute lymph throughout the lymph node. These sinusoids rejoin to form a single efferent lymphatic channel that drains lymph from the lymph node. The efferent lymphatic is located at the hilum of the lymph node.

The hilum of the lymph node also contains the artery and vein that supply the lymph node. Young B cells and T cells arriving at the lymph node do so via this artery. Lymphocytes that leave the lymph node either to patrol in the blood or to enter battle do so via the vein.

The lymph node is organised into B cells and T cell zones.

The B cells are distributed mainly around the periphery of the lymph node in lymphoid follicles. In a dormant lymph node, these follicles are relatively small and are known as primary follicles. If the B cells of the lymph node become active, the follicles develop into secondary follicles. Secondary follicles are dominated by a central germinal centre. The germinal centre is the site in which young B cells undergo training to become producers of effective immunoglobulins and is thus the place in which

B cell hypermutation takes place.

The germinal centre is surrounded by the darker mantle zone. This contains the B lymphocytes that have graduated from the germinal centre training camp. The mantle zone is usually eccentrically placed relative to the germinal centre, being thicker on part of the circumference of the germinal centre. This asymmetry is known as polarity.

The germinal centre contains specialised cells which assist the development of B cells. Follicular dendritic cells have receptors for the Fc portion of immunoglobulins and complement. This allows them to concentrate any antigen that arrives in the lymph node with immunoglobulin or complement bound to it and thus bring the antigen to the attention of the germinal centre B cells. Follicular dendritic cells are positive for CD21, CD23 and CD35.

The other assistant cells in the germinal centre are the tingible body macrophages. These are visible on H+E stained sections as large cells that possess clear cytoplasm in which dark blobs are present. Tingible body macrophages are antigen presenting cells. They engulf antigen, process it and present it on their surface to the germinal centre B cells. While B cells are readily able to detect raw antigen without the need for it to be processed, they are not averse to interacting with processed, presented antigen and the tingible body macrophages therefore enhance the exposure of the germinal centre B cells to antigen.

Germinal centre B cells which fail to develop a useful antibody die by apoptosis. They therefore do not express the antiapoptotic protein bcl-2. B cells which have matured beyond the germinal centre stage do express bcl-2. Germinal centre B cells are positive for CD10.

The zone between the follicles is appropriately named the interfollicular region. This is where the T cell inhabitants of the lymph node are predominantly located. They are exposed to antigen by antigen presenting cells that line the sinusoids. A few T cells permeate the germinal centres, presumably in their capacity as co-ordinators of the immune response in order to keep an eye on the young B cells.

|

|

|

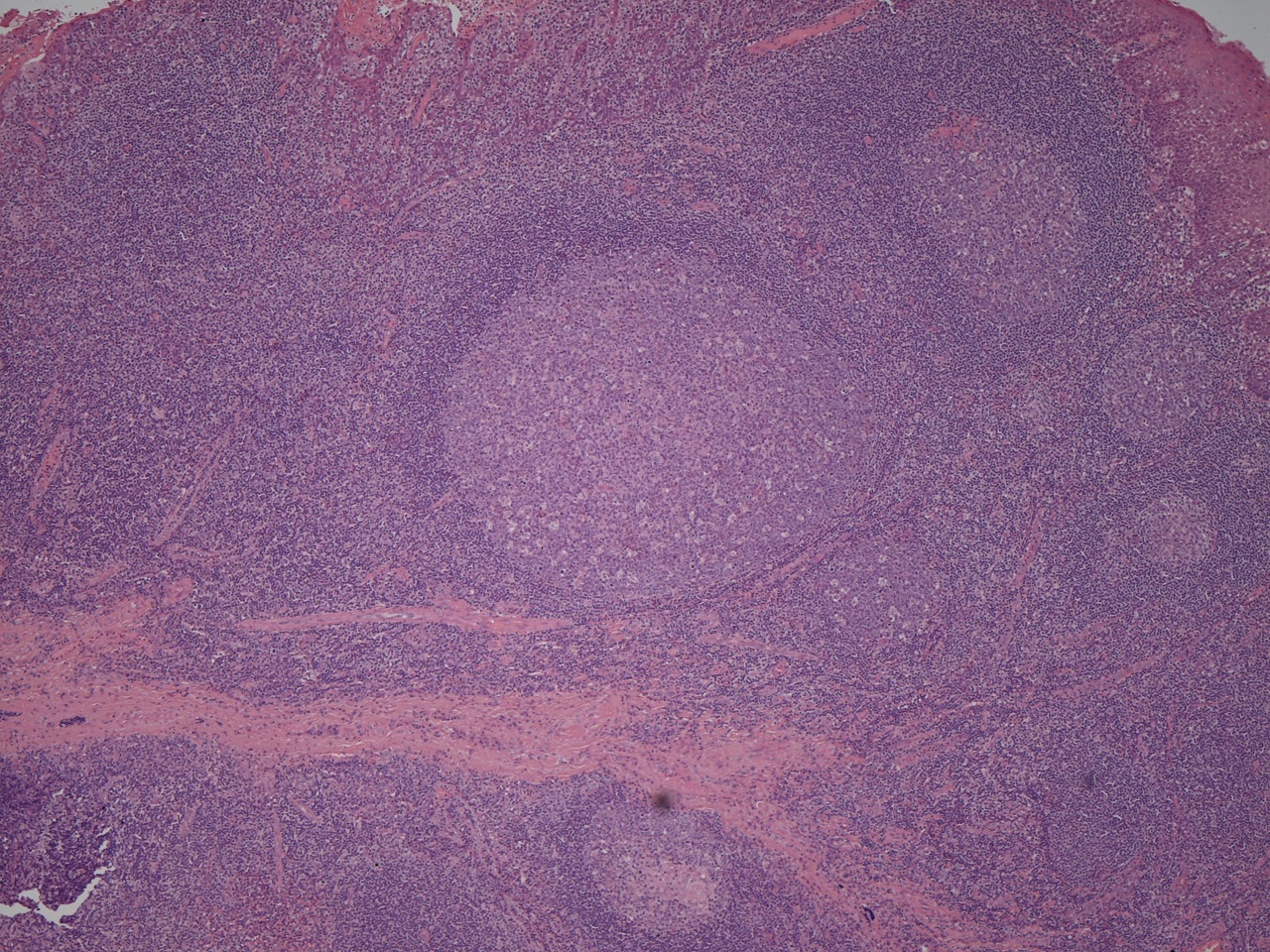

This photograph of the basic follicular and interfollicular architecture of lymphoid tissue is from a tonsil, which often displays the pattern well; other than the squamous epithelium towards the top of the picture, a lymph node would look similar.

A germinal centre is present in the centre of the image.

|

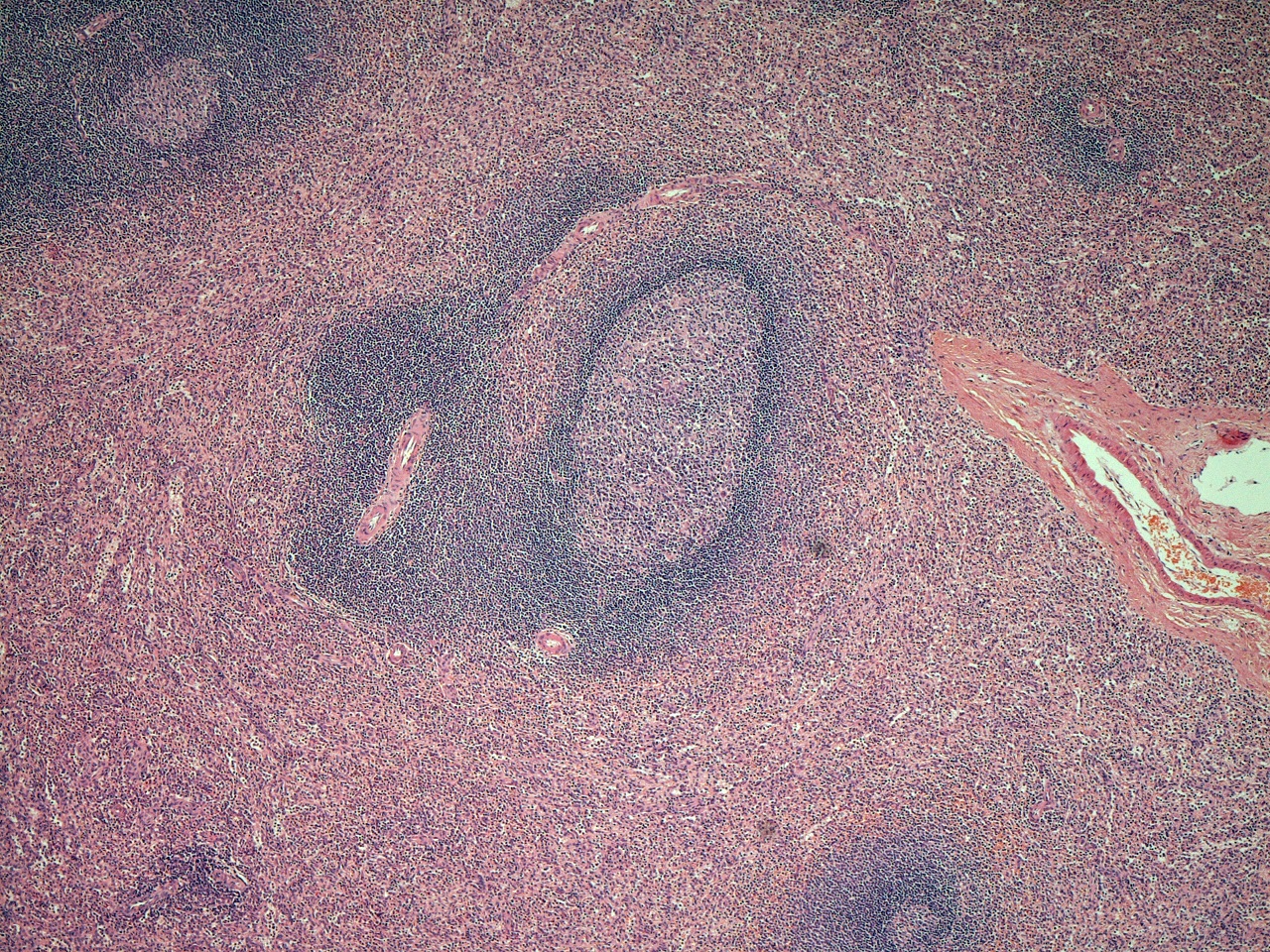

This close up of the lymphoid follicle from the left hand picture demonstrates the germinal centre outlined in light green and the outer edge of the mantle zone in dark green. The yellow arrow heads denote tingible body macrophages.

|

The Spleen

|

The spleen is a rather neglected organ that is typically handled somewhat like the remote cousin who is invited to Christmas dinner out of a sense of duty but tends to end up sitting in a corner having been engaged in only a few cursory conversations by the rest of the family. This may in part relate to the fact that there are no diseases that readily spring to mind as being primary to the spleen (except splenic marginal zone lymphoma, which is likely only to be familiar to haematologists and histopathologists and is in itself a rare lymphoma). Instead, the spleen is reduced to being an organ that can be involved in other diseases which usually manifest themselves as splenic enlargement (splenomegaly). The spleen can also suffer rupture, either due to trauma or in response to little or no provocation in acute infection with Epstein-Barr virus. Splenic infarction may also develop, mainly in sickle cell anaemia.

|

|

To compound the situation, the spleen is seldom biopsied partly because its anatomy, which may be a little simplistically and rather colloquially described as a 'bag of blood', does not tolerate biopsy well without a risk of haemorrage that may require surgery to control. Furthermore, it is usually not necessary to remove the spleen to obtain a diagnosis; those conditions that are associated with splenomegaly will typically have declared themselves by the clinical picture or through other less drastic investigations. These factors mean that splenic biopsies (usually aspirates) and splenectomy specimens are rare and this lack of familiarity does not facilitate understanding or appreciation.

As a final comment on the spleen's rather forlorn status in medical literature, the entire spleen can be removed with very few long term effects. The only real problem is an increased susceptibility to infection with certain encapsulated bacteria (Neisseria meningitidis and streptococcus pneumoniae) and this can be addressed by the astute use of vaccinations, although should not be blithely dismissed.

Despite the spleen's unusual standing in medical textbooks and practice, it remains a useful component of the immune system. In some respects it can be considered to execute a similar function for blood that lymph nodes discharge for lymph, namely that of a monitor.

The spleen has two components, the red pulp and the white pulp. The white pulp resembles numerous miniature lymph nodes scattered throughout the spleen in that each focus of white pulp has a lymphoid follicle composed of B cells and an associated T cell population that lines the small arteriole which feeds the follicle. This arrangement allows the lymphocytes of the white pulp to scrutinise the blood in the same way that the architecture of the lymph node permits them to peruse the lymph.

The red pulp is composed of a network of capillaries and more dilated vascular spaces (sinusoids) that are lined by macrophages. The macrophages remove old, decrepid erythrocytes from the circulation, break them down and salvage the iron from the red cells' haemoglobin. They also remove old platelets.

|

|

|

White pulp is shown in the centre of the photograph and is surrounded by red pulp. Other foci of white pulp are present at the 1 o'clock, 5 o'clock and 11 o'clock positions. Feeding arterioles are visible running around the left side of the central aggregate of white pulp.

|

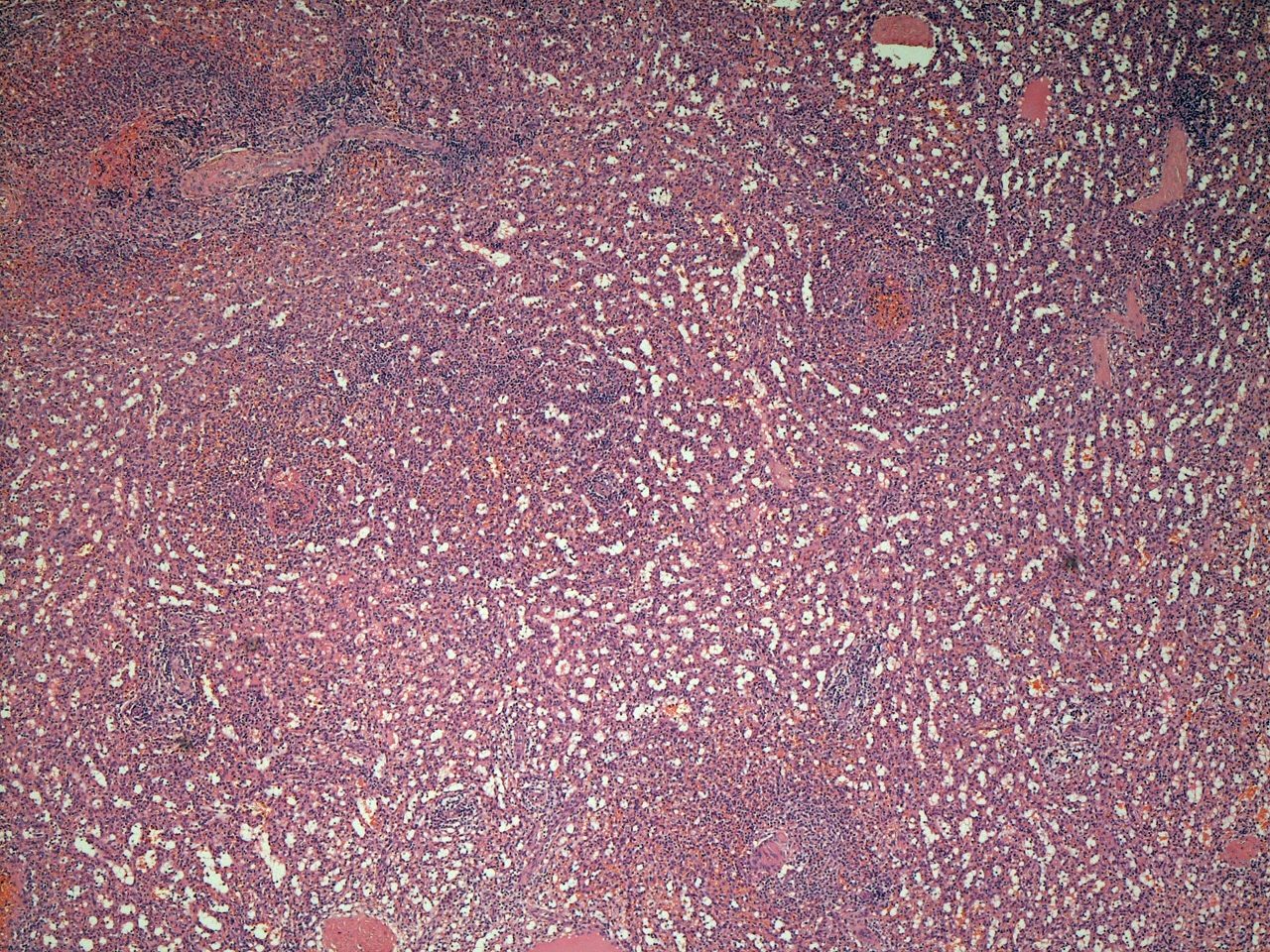

This image of the microscopic architecture of the spleen demonstrates the sinusoids of the red pulp. The sinusoids are often not this clearly demarcated.

|

One of the most well known lists in undergraduate medicine is the causes of massive splenomegaly. Massive splenomegaly may be defined as enlargment of the spleen to the degree that is extends from its usual location in the left flank under the left ninth, tenth and eleventh ribs all the way down and across into the right iliac fossa. This is a useful definition because it means that massive splenomegaly can be established simply by clinical examination.

The core list of causes of massive splenomegaly is as follows. Other diseases are added from time to time as rare causes (such as chronic lymphocytic leukaemia0.

- Myelofibrosis

- Chronic myeloid leukaemia

- Visceral leishmaniasis

- Malaria

- Gaucher's disease

Mucosa Associated Lymphoid Tissue

Mucosa associated lymphoid tissue (MALT) is found in a variety of organs, particularly the gastrointestinal tract. It is composed of aggregates in the mucosa of lymphoid tissue that recapitulate the follicular and interfollicular arrangement of lymph nodes. This lymphoid tissue is exposed to the the antigens that come into contact with the mucosa. Thus, for the GI tract the mucosa associated lymphoid tissue monitors ingested antigens. The mucosa associated lymphoid tissue is the principle site at which IgA is found.

Reticuloendothelial System

The reticuloendothelial system is the collective name applied to the bone marrow, lymph nodes, spleen, mucosa associated lymphoid tissue, thymus, tonsils and lymphatic channels. It encompasses most of the anatomical structures that contribute to the acquired immune system. The liver can also be included.

The tonsils are aggregates of lymphoid tissue that are located in the lateral wall of the oropharxynx, between the palatoglossal arch in front and the palatopharyngeal arch behind. They are covered by stratified squamous mucosa. The organisation of their lymphoid tissue follows the standard follicular and interfollicular architecture of the lymph node. The mucosa invaginates into the lymphoid tissue in numerous folds which increase the surface area available for antigen exposure.

The adenoids are similar structures to the tonsils that are located in the nasopharynx.