Contents

Introduction

Anaemia is the term used to indicate that a blood haemoglobin less than the lower limit of the normal range (under 13g/dL for males and below 11.5g/dL for females). Anaemia is a common problem but is often only secondary to an underlying disease rather than being the sole disorder. There are numerous causes of anaemia and assorted overlapping systems can be used to classify these causes.

Synthesis of Haemoglobin and Erythrocytes

Some of the basic categories of anaemia can be understood if the process by which haemoglobin and erythrocytes are made is understood.

Erythrocytes are synthesised in the haematopoietic

bone marrow. The creation of red blood cells is stimulated by the hormone erythropoietin (EPO) which is manufactured in the kidney.

The huge quantity of cell division which occurs in the bone marrow requires adequate supplies of substances that are integral to the synthesis of DNA. From the perspective of anaemia two key players are vitamin B12 and folate; general malnutrition will also deprive the bone marrow of the amino acids, carbohydrates and lipids which are essential for basic cell metabolism that is a prerequisite for cell division but in such instances of generalised malnutrition the anaemia is only one of many problems whereas deficiences of folate or vitamin B12 have narrower clinical features.

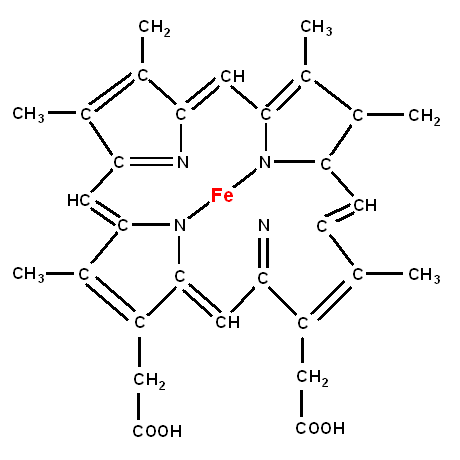

The globin portion of haemoglobin requires an iron molecule.

Once the erythrocytes have been made they enter the peripheral blood and have a life span of approximately 120 days. The bulk of the destruction and removal of old red cells occurs in the spleen but passage through any narrow blood vessel can impose stresses on the erythrocytes such that if a splenectomy is performed the body can still deal with decrepit red cells.

|

|

Globin

|

Classification

There are various categories of anaemia. These categories tend to overlap and any given type of anaemia may be a member of more than one category.

Red Cell Indices

One of the most commonly employed classifications describes the anemia in terms of the mean cell volume and the mean corpuscular haemoglobin concentration. In some forms of anaemia either the MCV and/or the MCHC is/are abnormal such that the red cells may be smaller (microcytic) or larger (macrocytic) than normal and/or have a lower concentration of haemoglobin than normal (hypochromic). The terms normocytic and normochromic are used to denote types of anaemia in which the MCH and MCHC respectively are normal.

Hypochromic, microcytic anaemia implies either iron deficiency or thalassaemia as the cause.

Macrocytic anaemias are likely to be due to folate deficiency, vitamin B12 deficiency or myelodysplasia (nevertheless, macrocytosis is not compulsory in this entity). The MCV is also elevated in haemolytic anaemia but the erythrocytes themselves are not larger than normal. Instead, the bone marrow responds to the destruction of red blood cells by pumping out reticulocytes, which are the immediate precursor form of erythrocytes. Reticulocytes are larger than erythrocytes but look like erythrocytes to the automated cell analysers that perform the full blood count and thus skew the average MCV up.

A macrocytosis can also result from alcohol and hypothryoidism, although anaemia is often not present.

Haemolysis

Various diseases render red cells prone to destruction and cause them to have a shorter lifespan. If the degree of erythrocyte destruction is sufficient then the bone marrow cannot keep up and the haemoglobin falls. The premature or excessive destruction of red cells is referred to as haemolysis and many types of anaemia are haemolytic in nature.

Haemoglobinopathies

The two main haemoglobinopathies are thalassaemia and sickle cell disease. Both are also congenital anaemias. In haemoglobinopathies the amino acid sequence of haemoglobin is abnormal and this interferes with the function of the haemoglobin.

Intrinsic Erythrocyte Defects

Erythrocytes which are produced in a defective form are liable to have a shorter life span; anaemias caused by intrinsic problems in the erythrocytes are also usually haemolytic. With the exception of paroxysmal nocturnal haemoglobinuria they are also typically congenital.

Bone Marrow Failure

Even if red cell survival in the peripheral blood is normal anaemia will still occur if the bone marrow does not produce enough erythrocytes in the first place. This can occur if the bone marrow is destroyed, replaced by an infiltrate or has an isolated deficiency of erythropoiesis (pure red cell aplasia).

Congenital and Acquired

The division of aetiologies into congenital and acquired categories is one of the oldest chestnuts in medical education. It is often not the best way to classify causes and anaemia is no exception. However, despite its limitations, the allocation into the congenital and acquired camps does provide another framework in which to consider anaemia.

Causes of Anaemia

The following list of the causes of anaemia will use some of the categories described above.

- Macrocytic

- Folate deficiency

- Vitamin B12 deficiency

- Myelodysplasia (some cases)

- Hypochromic microcytic

- Iron deficiency

- Thalassaemia

- Haemolysis

- Automimmune haemolytic anaemia

- Sickle cell anaemia

- Glucose-6-phophate dehydrogenase deficiency

- Pyruvate kinase deficiency

- Hereditary spherocytosis

- Hereditary elliptocytosis

- Paroxysmal nocturnal haemoglobinuria

- Drugs

- March haemoglobinuria

- Malaria

- Prosthetic heart valves

- Thrombotic thromocytopenic purpura

- Haemolytic uraemic syndrome

- Haemoglobinopathies

- Thalassaemia

- Sickle cell anaemia

- Intrinsic Erythrocyte Defects

- Glucose-6-phophate dehydrogenase deficiency

- Pyruvate kinase deficiency

- Hereditary spherocytosis

- Hereditary elliptocytosis

- Paroxysmal nocturnal haemoglobinuria

- Bone Marrow Failure

- Aplastic anaemia

- Leukaemia

- Myeloma

- Lymphoma

- Metastases

- Myelodysplasia

- Myelofibrosis

- Folate deficiency

- Vitamin B12 deficiency

- Pure red cell aplasia

- Congenital

- Thalassaemia

- Sickle cell anaemia

- Glucose-6-phophate dehydrogenase deficiency

- Pyruvate kinase deficiency

- Hereditary spherocytosis

- Hereditary elliptocytosis

- Paroxysmal nocturnal haemoglobinuria

- Miscellaneous

- Anaemia of chronic disease

Anaemia of chronic disease can develop in a variety of inflammatory conditions and is a consequence of one of the body's antimicrobial defences. During an infection the body reduces the release of iron from the reticuloendothelial system and instead keeps it locked up. This retention of iron is intended to deprive micro-organisms of access to the iron. However, in a non-infectious chronic inflammatory disease the iron-hiding mechanisms employed by the inflammatory cells are also stimulated. Despite the role of iron deprivation in the anaemia of chronic disease it tends to be a normochromic normocytic anaemia.

Clinical Features

Mild degrees of anaemia may be asymptomatic and only apparent if a full blood count is performed. However, more marked anaemia causes pallor which may first be noticed in the mucous membranes such as the conjunctiva.

Anaemia is associated with a reduction in the oxygen-carrying capacity of the blood and a profound anaemia can cause breathlessness. Rarely, angina or high output cardiac failure can result. More commonly the patient may complain of feeling tired or easily fatigued.

Headaches may occur.

The retina may display haemorrhages or papilloedema.

Anaemia which develops gradually may be better tolerated than that which has a more rapid onset.

The features of the condition which has produced the anaemia may also be present.

Investigations

The full array of investigations that relate to anaemia is wide and it is unusual that any given patient will require all of them.

The opening investigation is the full blood count. This determines if anaemia is present, establishes its degree and also discloses the red cell indices (mean cell volume and mean corpuscular haemoglobin concentration). The MCV and MCHC alone can be very helpful in guiding what happens next.

A blood film can be made from a sample of the peripheral blood and the haematology laboratory may proceed to one if the full blood count is abnormal. The film can given an indication of red cell size, erythrocyte shape and chromasia. The other components of the blood are also visible. The film is particularly useful if a primary bone marrow problem is suspected. It is also a key investigation in malaria (regardless of whether anaemia is present).

Vitamin B12 and folate are referred to as the haematinics. Even if the MCV is normal they are often measured because the anaemia may have more than one cause where the second causes masks the macrocytosis. For example, iron deficiency and folate deficiency may co-exist (in this case the blood film will show a dimorphic picture where individual erythrocytes may be microcytic or macrocytic). Furthermore, even if the anaemia is mainly due to another condition, correcting low vitamin B12 or folate levels may assist recovery.

Iron studies can also be requested.

Haemoglobin electrophoresis is a technique that analyses the composition of haemoglobin and can disclose abnormal forms. Its main role is in determining if the patient has sickle cell anaemia or thalassaemia.

Assorted investigations may be performed to address haemolysis and are discussed in the section for haemolytic anaemia.

The urea and electrolytes should be checked to exclude chronic renal failure as the cause or as a contributing factor.

Many patients who have anaemia will not require a bone marrow trephine because the origin of the anaemia will have become apparent from the history, examination and simpler investigations. The trephine is reserved for patients in whom primary bone marrow disease is suspected or who have resisted attempts to establish the cause of their anaemia.

Treatment

The treatment of the anaemia is to address the underlying cause and to deal with any nutritional deficiencies. Blood transfusion tends to be reserved for symptomatic anaemia, severe anaemia or instances of blood loss due to haemorrhage.